There is an Hour when I must die,

Nor do I know how soon ’twill come;

Let me improve the Hours I have,

Before the Day of Grace is fled;

There’s no repentance in the grave,

No pardon offer’d to the dead.

From Solemn Thoughts on God and Death by Isaac Watts (1674-1748)

Illustration by Robert Crumb

Click on the LINKS to find out more…..

GRAVES

CHAPEL GRAVES

PUBLIC or COMMON GRAVES

William Christian – Potter’s Field – Hart Island

GRAVEDIGGERS

* * *

GRAVES

It is traditional in many Christian denominations for people to be buried on an east-west axis, with their head to the west, lying on their back, so that they will be able to rise up and witness the Second Coming of Christ in the east.

Rise, Dead and Come to Judgement

Jacques Gamelin, 1779

‘For as the lightning cometh out of the east, and shineth even unto the west; so shall also the coming of the Son of man be’. (Matthew 24:27)

There is also a tradition, particularly in the Catholic church, that priests should be buried facing west, so that they will rise up facing their flock.

At Wainsgate the graves are laid out on a roughly east-west axis, but with the heads to the east, presumably because of the slope of the ground. Those who rise up on the Last Day will be facing in the wrong direction to witness the Second Coming, but as a consolation will instead have wonderful views of the hills across the Calder valley.

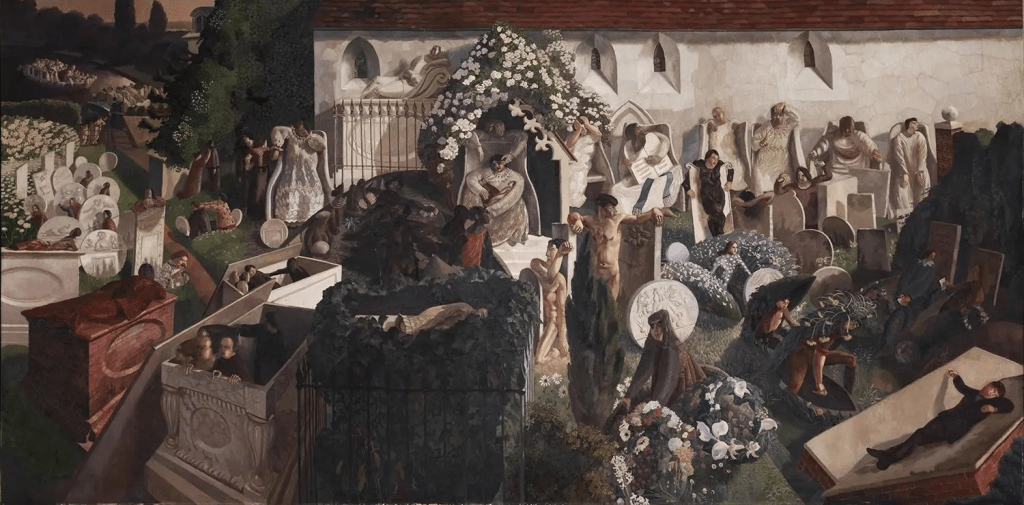

The Resurrection, Cookham (1924–7) by Stanley Spencer

Most of the newer graves at Wainsgate have only one or two burials in them, but most of the older graves contain more: the largest number of burials in a single grave plot so far identified at Wainsgate is ten.

The headstone on plot CY375 records ten people, although one of them, George Jackson, may be buried elsewhere (in plot B138a) and five of those buried are infants or young children:

Monumentum

of HANNAH, wife of JOHN

JACKSON of BOSTON HILL, who died

Sept 8th 1837 Aged 28 Years.

ALSO the abovenamed JOHN JACKSON,

who died Aug 27th 1841 Aged 33 Years.

ALSO two of their Children, who

died in infancy.

———————-

IN MEMORY OF

WILLIAM, son of GEORGE and SARAH

JACKSON and grandson of the

above who died Dec 7th 1862,

Aged 4 years and 7 months.

Also of BEN their son who died

Feb 1st 1868, Aged 8 months.

ALSO of JANE daughter of the above,

who died Dec 25th 1876, in her 4th year.

ALSO of HANNAH their daughter

who died March 20th 1884

in her 20th year.

ALSO of the above GEORGE JACKSON,

who died Oct 23rd 1890, aged 57 years.

ALSO of JAMES their son who died July 3rd

1888, in his 18th year.

There is another grave (B8a) with nine people known to be buried in it: Thomas Wilcock. a fustian weaver of Nutclough, Hebden Bridge (died 1909, aged 62), his wife Grace (died 1924, aged 76) and seven of their children. The children are not named on the headstone, but research into burial and other records has identified probable names and dates – it is thought that they died between 1872 and 1893, and only one lived beyond one year old.

The seven children are thought to be: Benjamin (died 1872 aged 11 months), Wilbert (died 1875 aged 4 weeks), Edith Ann (died 1878 aged 1 year), Ernest (died 1880 aged 1 year), Frank (died 1886 aged 14 months), Bertha (died 1886 aged 3 years) and George Herbert, who died in 1893 aged 10 months.

Thomas and Grace seem to have had four other children who survived to adulthood: James Moses Wilcock, Mildred, Frederick, and the wonderfully named Admiral Wilcock.

CHAPEL GRAVES

There are ten grave plots which were bought by Wainsgate and Hope Chapels, presumably for burials of ministers and others associated with local Baptist churches.

Plots A507, A508, A509, A510, A511 & A512: Bought by ‘Trustees of Hope Chapel, Hebden Bridge’. The date in the burial register is 27th October 1881, but this is probably incorrect. Plots A507, A508, A509 & A510 appear to be unused.

Plot A511 contains the grave of Rev. Peter Scott, who died in 1866 and was minister at Brearley Baptist Church from 1853 to 1865, and Caroline Ibberson, who died in 1880 aged 13 months. Caroline was the daughter of Rev. William Henry Ibberson, pastor at Hope Chapel from 1877 to 1881.

Plot A512 contains the grave of Rev. John Crook, minister at Ebenezer and Hope Baptist chapels in Hebden Bridge who died in 1861, and his wife Mary, who died in Southport in 1877.

Plots A537, A538, A539 & A540: Bought by ‘Wainsgate Church – for Ministers etc.’ There is no date in the receipt book, and the receipts are still in the book. These four plots appear to be unused – the three Wainsgate ministers known to be buried in the graveyard (Richard Smith, John Fawcett and James Jack) are buried elsewhere.

PUBLIC or COMMON GRAVES

There are a number of graves which appear not to be private graves, bought by individuals for themselves or their family, but were bought either by public bodies or by individuals, presumably with philanthropic intent. Whilst there are no definitive records of burials in these plots, it is assumed that they were intended for use as ‘public’ or ‘common’ graves, for people who could not afford to buy their own grave plot.

The Poor Mans Friend : cartoon by John Leech from Punch, 1845, showing Death as the friend of the old or sick unemployed manual labourer, a more welcome option than the Workhouse that can be seen through the window.

Plots A379, A380, A381 & A382: The receipt book records these four plots being bought on 31st May 1881 (this is almost certainly incorrect, and they were probably bought around 1860) by ‘M.E. Cousin’ – assumed to be Mary Elizabeth Cousin of Boston Hill. There is no record of burials in these plots, and no headstones or other markers, and they appear to be unused.

Plot A407: Bought by ‘Wadsworth Town’. Date not recorded, possibly around 1856.

Plot A463: Bought by ‘Wadsworth Town’. Date not recorded, but before 1875.

Plots A559, A561, A574 & A575: Bought by ‘Wadsworth Township’. Dates not recorded, but before 1875.

Plots B345a, B346a, B347a, B348a, B357a, B358a, B359a, B360a, B1186 & B1187: This block of ten plots was bought by ‘Miss Mitchell, Boston Hill’ (presumably Clara Mitchell) on 5th November 1920. There is a small square stone marked CM at each corner of the area. There is evidence that at least some of these plots have been used for burials, although there are no headstones or marker stones.

It is possible that these plots were bought by Miss Mitchell at the time of the 1920 Oxenhope Charabanc Disaster: one of the victims, Henry Drake Turner, was buried on 4th November 1920, and it is believed that he was buried in a public or common grave, perhaps one of these.

One of the receipt books shows that on 12th May 1924, J. W. Martin of Chiserley Field Side was given permission (for a fee of 5 shillings) to bury a ‘still born child‘ in plot B363a. The burial register records the burial taking place on 10th May. The grave was used for two more burials: a stillborn child of F. J. Greenwood, Hebden View, was buried on 28th January 1925, and Raymond Clarke of 1 Old Town Cottages was buried on 24th July 1931, aged 13 days.

A note written on the stub of the receipt book says ‘belongs to Graveyard Trustees’, implying that this is a public or common grave. We know nothing about the two stillborn babies – whether they were male or female or whether they were named by their parents. Stillbirths were not formally registered until 1st July 1927, and records are not publically available. We know little about Raymond: his birth and death were registered in Todmorden Registration district and his mother’s maiden name was Robinson.

The two stillborn babies were buried without an officiating minister, something which is true of several other similar burials at Wainsgate. We don’t know whether anyone else was buried in this plot. The grave is unmarked.

* * *

There is only one known common or public grave in the ‘new’ graveyard: plot D1013 was bought by Hebden Royd Urban District Council on 29th December 1951. The burial register has one entry for that day – William Christian, aged 71, of 4 High Street, Hebden Bridge. The grave is unmarked.

William Christian was born at Dodworth, near Barnsley, in 1880. He married Mabel Gertrude Secker in 1907: at the time of his marriage both William and Mabel were living at North Elmsall station: he was a signalman and William’s father, John Christian, is recorded on the marriage certificate as a stationmaster. In 1939 William and Mabel were living at 1 Station Cottages, Ferriby, near Hull: he was a signalman for the London & North Eastern Railway, their son John was a railway porter, and daughter Nellie a railway clerk.

In the 1951 Electoral register, William was living at 4 High Street, Hebden Bridge, but not with his wife Mabel – she was still alive, and when she died in 1967 was recorded as living at 1 Railway Cottages, North Ferriby. William was living in a lodging house when he died: the Electoral Register for 1951 lists five other men living at that address – Dominic Collaran, Smith Dewhirst, Frank Jarvis, Timothy Mattimore and James Temprol (who seems to have changed his name at some time from James Burton).

Why was William Christian living in a lodging house in Hebden Bridge when he died? His wife was probably living with John or Nellie, at least one of whom was presumably still working for British Railways (LNER had been nationalised in 1948). Was he working away in Hebden Bridge, or had he separated from his wife and family? Why was he buried in a common grave provided by by the local council? Was he the only person buried in this grave: the burial register records a number of people buried after 1951 for whom a grave has not been identified, and some of these may also be buried in plot D1013 with William Christian.

* * *

POTTER’S FIELD & HART ISLAND

Potter’s field is the name often given to a place of burial for unknown, unclaimed or indigent people, or for those whose families could not afford the cost of a ‘proper’ burial. The origin of the name is biblical (Matthew 27:3–27:8, in which Jewish priests take the 30 pieces of silver returned by a remorseful Judas). The priests considered it to be ‘blood money’ which could not be put into the temple treasury, and so used it to purchase a plot of land for the burial of ‘strangers, criminals and the poor’.

The field purchased for the burial ground was previously used by potters to excavate red clay, and is thought to be located in the valley of Hinnom, near Jerusalem. The site was thereafter known as Akeldama – ‘field of blood’ in Aramaic.

Left: The Trench in Potter’s Field (c1890) by Jacob Riis. Right: Potter’s Field monument, Hart Island, New York.

Hart Island, a small island in Long Island Sound, northeastern Bronx, New York City is the largest municipal cemetery in the United States and is one of the largest ‘potter’s field’ cemeteries in the world. Burials started in 1869, and continue to this day. Around 1,000,000 people are buried there, including individuals who were not claimed by their families or did not have private funerals; the homeless and the indigent; and mass burials of disease victims. Many of those buried there are infants and stillborn babies.

Bodies are buried in large trenches, between three and five coffins deep, each containing between 100 and 150 adult bodies. The coffins are crude pine boxes, each identified with an identification number and, where possible, the person’s age, ethnicity, and the place where the person died or the body was found. Until 2020, burials were carried out by prisoners from nearby Rikers Island prison.

In 1985 the bodies of 16 people who had died from AIDS were buried in graves about 14 feet deep (as deep as they could be dug before hitting bedrock) on a remote section of the southern tip of the island – at the time it was feared that their remains may be contagious. In 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, Hart Island was designated as the temporary burial site for people who had died from COVID if deaths overwhelmed the capacity of new York City mortuaries.

Left: Photo by Claire Yaffa / New-York Historical Society. Right: Burial of victims of COVID-19, April 2020.

In 2011, New York artist Melinda Hunt, who had first visited the island in 1991, launched The Hart Island Project. This inspirational project aims to raise awareness and understanding of the cemetery and to facilitate access to the island and the cemetery records. The project has mapped the entire island, scanned and digitised records, provides access to information about the burials on Hart Island, tools and workshops for storytelling as well as personal support to families of the buried.

GRAVEDIGGERS

He took off his coat, set down his lantern, and getting into the unfinished grave, worked at it for an hour or so with right good-will. But the earth was hardened with the frost, and it was no very easy matter to break it up, and shovel it out; and although there was a moon, it was a very young one, and shed little light upon the grave, which was in the shadow of the church. At any other time, these obstacles would have made Gabriel Grub very moody and miserable, but he was so well pleased with having stopped the small boy’s singing, that he took little heed of the scanty progress he had made, and looked down into the grave, when he had finished work for the night, with grim satisfaction, murmuring as he gathered up his things –

Brave lodgings for one, brave lodgings for one,

A few feet of cold earth, when life is done;

A stone at the head, a stone at the feet,

A rich, juicy meal for the worms to eat;

Rank grass overhead, and damp clay around,

Brave lodgings for one, these, in holy ground!

“Ho! ho!” laughed Gabriel Grub, as he sat himself down on a flat tombstone which was a favourite resting-place of his, and drew forth his wicker bottle. “A coffin at Christmas! A Christmas box! Ho! ho! ho!”

From The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton by Charles Dickens

Illustration by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne)

* * *

There is only one mention of gravediggers in the Burial Register: following the entry for 17th October 1850, the burial of ‘Mrs. Fawcett, wife of John Fawcett junior‘, it says:

‘This was where Jno Wadsworth gave up grave digging’.

It has not been established who John Wadsworth was, when he started digging graves at Wainsgate and why he dug his last grave on 17th October 1850. We also don’t know whether or not he was himself buried at Wainsgate.

FIRST GRAVEDIGGER: What is he that builds stronger than either the mason, the shipwright, or the carpenter?

SECOND GRAVEDIGGER: The gallows-maker; for that frame outlives a thousand tenants.

FIRST GRAVEDIGGER: ………. when you are asked this question next, say ‘a grave-maker: the houses that he makes last till doomsday’.

Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 1

Grave-digger by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1871