A charabanc carrying thirty-seven people set off from the Robin Hood Inn, Pecket Well shortly after noon on the 30th October 1920, bound for a knur-and-spell game at Laneshaw Bridge, near Colne. The 32-seat charabanc, built by the Maudslay Motor Company of Coventry, was the last of several such vehicles to leave the Hebden Bridge area, taking people from Wadsworth and Pecket Well to the game. The vehicle was owned by Messrs Greenoff & Shaw of Rochdale, and the outing was organized by John Murgatroyd, landlord of the Robin Hood Inn.

During the steep descent from Cock Hill to Oxenhope, the brakes failed to slow the vehicle, which left the road and crashed through the wall on the sharp left hand bend above Oxenhope church. Five passengers were killed and many injured, four of them seriously.

John Murgatroyd’s description of the accident was reported in the Keighley News:

“After going down the far slope for a quarter of a mile the driver tried to check the growing speed of the char-a-bancs. He applied both the foot and hand brakes to the full without checking the vehicle. It was an awful experience, for the motor was gaining speed at every yard. The driver held on to his steering wheel, and marvellously got round a couple of sharp bends. All the passengers must have realised that they were being carried along at a break-neck speed, but they remained calm, and there was no sign of panic. As we bowled on to the last long straight stretch, the char-a-bancs must have been going at forty miles an hour, and at the end was the hair-pin bend. No man breathing could have got a motor round at the speed at which we were travelling. As we approached the end I shut my eyes and awaited the end. It was an awful shock. Practically all were hurled out of the car, and I dropped in a field about twenty yards away.”

The Keighley News also reported:

“One passenger, more daring than the rest, when he saw an accident was unavoidable, jumped from the rapidly-moving vehicle into the road. He rolled head over heels time and time again, and another passenger who was going to jump thought the man was killed, and decided not to leap, and crouched down behind a seat. He was practically unhurt, and the man who jumped received only slight injuries to the arm”.

“All the passengers and debris from the vehicle, the wall, and from a hen-house which was in the field immediately behind the wall, were thrown into an indescribable heap. Thrown on to a heap of stones and against the trees the passengers sustained shocking injuries. Two passengers were picked up dead, and others were unconscious. The noise of the collision and the screams of the injured brought the villagers to the scene, and help was quickly rendered. Dr. McCracken, of Haworth, was in the village at the time and he was soon on the spot. Policemen, members of the St. John Ambulance Brigade, and nurses were on the scene quickly, and Dr. Maggs and Dr. Wilson, of Haworth, were summoned by telephone. A motor-ambulance from the Keighley Fire Station was called, and in this, on on a motor-lorry owned by Messrs. Merrall, spinners, Haworth, a number of the serious cases were taken to the Keighley Victoria Hospital, where medical men were awaiting the arrival of the patients.

“The great force with which the motor char-a-bancs hit the wall can be judged by the appearance of the vehicle after the accident. The radiator shows the marks where the stones hit it, and one side is broken away. The front axle is broken and the steering column fractured, but it was along the right side of the body that most damage was done. The whole of the side is broken completely away, the woodwork being in splinters, and all the aluminium panelling broken and twisted in all directions. The ends of the seats are directly in view, and instead of remaining parallel they are twisted in all directions.”

Those killed were William Ogden (56), John Henry Drake Turner (43), William Devonport Kershaw (35), his wife Alice Kershaw (37) and Percy Brown Roe (30).

The names of the other passengers are not known, apart from two of those injured who gave evidence at the inquest, James McWhirter of Pecket Well and Charles Greenwood of Green End Wadsworth, John Murgatroyd, the organiser of the trip and John Graham who was treated at Victoria Hospital for fractured ribs and a badly damaged hand.

The driver, Tom Hay of Rochdale, who was slightly injured in the crash was cleared of blame, and it is thought the accident was caused by defective brakes. Members of the Oxenhope Division of the St. John Ambulance Brigade attended the accident, and were able to collect £14 from sightseers the next day, when postcard photographers flocked to the scene to record macabre (but best-selling) images like the one below.

The accident was raised in the House of Commons by the MP for Keighley, Sir Robert Clough, and an inspector from the Ministry of Transport visited the scene to make enquiries.

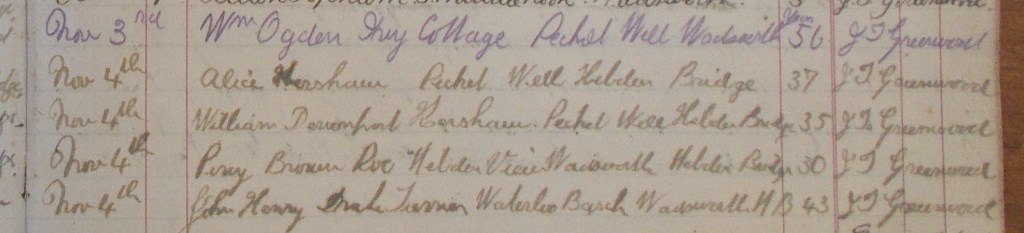

The five who died were all buried at Wainsgate: William Ogden on 3rd November, the others on 4th November. The burial services, and the memorial service held on Sunday 7th November were conducted by a local lay preacher, John Thomas Greenwood of Pecket Well. The chapel was packed to its full capacity for the memorial service, with their workmates and employers, survivors of the crash and members of Old Town Bowling Club in attendance, and it was reported that local schools, shops, pubs and businesses closed in honour of the dead.

There was a full choir (presumably conducted by A.R. Ashworth) and J.W. Parker played the organ. Hymns included ‘Our blest Redeemer, ere He breathed’, ‘Rock of Ages’, John Fawcett’s ‘Blest be the Tie that Binds’ and the funeral anthem ‘Crossing the Bar’, and the service concluded with the organist playing the ‘Dead March in Saul’ by Handel while the congregation stood with bowed heads. The Lessons selected by the preacher were Psalm 42 and 2 Samuel 18, which tells the story of the death of Absalom.

* * *

William Devonport Kershaw, born in Bradford, the son of William Wright Kershaw (a stone mason), was a mason’s labourer, living in Pecket Well with his wife Alice Kershaw (born Crump). Alice, born in Coventry, daughter of Joseph Crump (a bicycle maker), was living in Denholme when they married there in 1906. The couple were described at the memorial service as being:

‘kind and cheery in their disposition…..lively and pleasant in their lives, deeply attached to each other, and in death they were not divided’.

They are believed to have had two sons, George, born in 1907 and Charles Albert, born in 1910: both children almost certainly died in infancy. It also appears that William and Alice lived apart for a period of time – the 1911 census shows him boarding with the Shackleton family in Keighley, and his marital status is recorded as ‘widower’, and he also made no mention of being married when he enlisted with the Royal Irish Rifles in 1914. We don’t know when or why they separated, but it may have been before the birth (and death) of their second child – it is also possible that he wasn’t the father. They presumably got back together after he was discharged from the army in 1915.

Alice died at the scene of the accident and William died later that day at the Victoria Hospital, Keighley. Both bodies were identified by Alice’s mother, Mrs Jane Fletcher (she had remarried after her first husband’s death).

They are believed to be buried in plot C626. There is no headstone, and the plot, which was purchased on 3rd November 1920 by the couple’s executors, is identified by a marker stone with the initials J.F.

William Devonport Kershaw had previously been a professional soldier with the West Riding Regiment, and also to have enlisted with the Royal Irish Rifles in 1914, although his military service appears to have been brief and eventful: to find out more click here.

* * *

William Ogden, born in Manchester, was a millhand living at Ivy Cottage, Pecket Well. He was married to Hannah Jane (born Eyre), also from Manchester, and they had four children, Edith, Fleta, James and William. He is buried in plot E902, together with his wife (who died in 1925) and daughter-in-law Rachel, wife of James Ogden.

He died of his injuries on arrival at Victoria Hospital, Keighley.

William was described as being:

‘a living example of the beauty of unselfishness…..generous and most happy when helping others’.

* * *

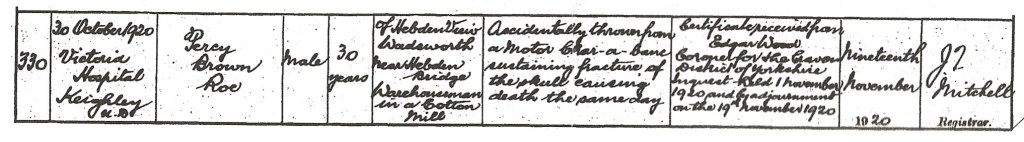

Percy Brown Roe, born in Addingham, was described on his death certificate as a ‘warehouseman in a cotton mill’, living at Hebden View, Wadsworth with his wife Alice (born Johnson). They married in 1915 and had three children, all of whom died in infancy: Catharine Mary, died in 1917 aged 2 months, Albany, died in 1919 aged 4 days and Wilfred died in March 1920 aged 2 months.

Percy’s death certificate states that he died at Victoria Hospital, Keighley and cause of death is given as ‘accidentally thrown from a motor char-a-banc sustaining fracture of the skull causing death the same day’.

Percy Roe is buried in plot C614, which has a Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone. He had been a regular soldier before the war, serving in India with the Durham Light Infantry, and was serving with them at the time of his marriage in 1915. Since his death was not attributable to his wartime service in the army, a CWGC headstone would indicate that he was serving in the armed forces at the time of his death, and the inscription describes him as a Serjeant in the Royal Engineers, presumably a volunteer in the Territorial Force.

Alice died in 1938, aged 47, and she and their children are buried at Wainsgate, presumably in Plot C614 with Percy. The plot was purchased by Alice on 31st January 1917, shortly before the death of their daughter Catharine Mary.

* * *

John Henry Drake Turner was born John Henry Drake in Queensbury in 1877, the son of Mary – whose maiden name was Turner, and who may (or may not) have been married to Joseph Drake, a stone mason. Mary was single in 1871, living in Swamp, Northowram with her widowed mother, her younger sister and her two year old son Harry Drake Turner. In 1881 she was recorded as being married to Joseph Drake, and had two children, twelve year old Harry (now called Harry Drake) and three year old John Henry Drake. In 1891 she was still recorded as being married to Joseph, and as well as John Henry they had six other children, all with the surname Drake. What is unclear is whether Mary ever married Joseph Drake, and if so, when: no records have been found of a marriage that could be theirs.

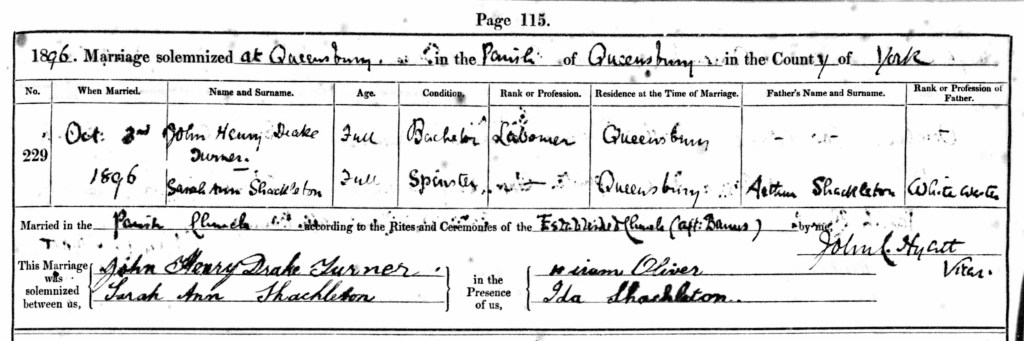

John Henry married Sarah Ann Shackleton in Queensbury in 1896 and they had eight children, all of whom had Drake as a middle name. His marriage certificate gives his name as John Henry Drake Turner, and does not state his father’s name or profession. So who was his biological father – was it Joseph Drake?

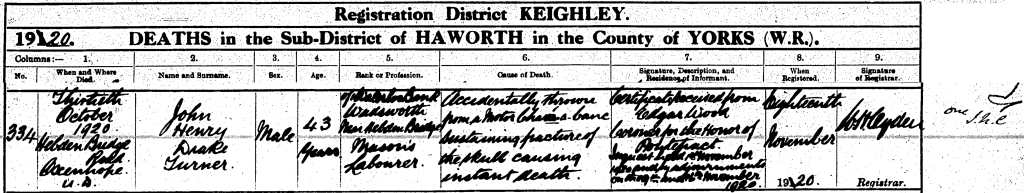

At the time of his death he was a mason’s labourer, and the burial register and death certificate record him living at Waterloo Bank, Wadsworth, although there is no record of him in the electoral register: perhaps he was lodging there temporarily and his family were living elsewhere. His death certificate states that cause of death was ‘accidentally thrown from a motor char-a-banc sustaining fracture of the skull causing instant death’.

Although his burial is recorded in the Wainsgate burial register, the exact location of his grave is unknown. It is likely that he was buried in an unmarked public or common grave: perhaps one of the ten plots bought by ‘Miss Mitchell’ (presumably Clara Mitchell of Boston Hill) on 5th November 1920.

It was reported in The District News that:

‘During the week end a crowd of people made a pilgrimage to Wainsgate and quietly filed past the graves of the victims’.

* * *

Two weeks later, a charabanc travelling from Skipton to Burnley left the road at Blacko, near Barrowford and crashed into the old Toll Bar House, killing five of the passengers. Stanley Turner, from Earby, who was on his way to spend the weekend with his aunt, was 16 years old. The other four men, all from Skipton – Archie Lee, 22, Harry Jones, 21, Fred Phillip, 22 and John Stephenson, 22, were travelling to a football match between Burnley and Newcastle at Turf Moor. It had been very much a day out: the charabancs had set off from Grassington before lunchtime, there had been stops at hotels along the way and the route to the Burnley ground had taken in picturesque Bowland.

The four men from Skipton were buried at Waltonwrays cemetery and Stanley Turner was buried in his home town of Earby. The funeral corteges of the men brought Skipton to a standstill as they passed through the town centre and up the High Street. Businesses were closed, blinds were drawn and flags were flown at half mast. Workers were given leave to attend the service and sympathisers from Skipton, Cross Hills, Cononley and Steeton lined the streets. At the conclusion of the service, a procession was formed including a detachment of ex-servicemen and Skipton Brass Band.

Four of those killed, just like Percy Roe, had survived fighting in the First World War, only to die in a charabanc crash. The driver, Frank Bailey from Burnsall was charged with manslaughter and being drunk in charge of a vehicle, but was later acquitted at Manchester Assizes. The cause of the crash, as was the case at Oxenhope, is believed to have been brake failure.

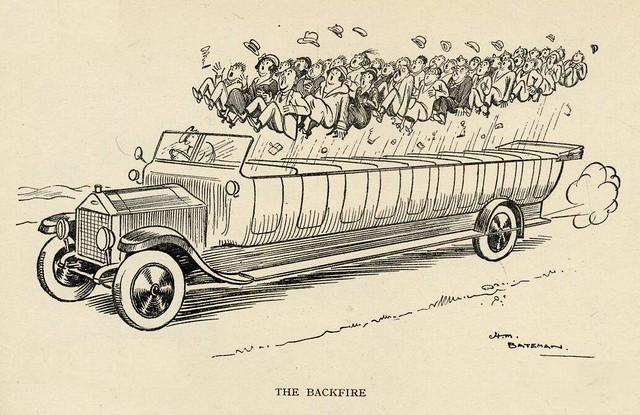

Most charabanc trips were sight-seeing excursions and annual factory outings, including jaunts to the countryside, major towns or the seaside, but the ‘menace’ of day-trippers (particularly working class day-trippers) became an issue as charabanc parties began invading posh seaside and spa towns. Many tours became mechanised pub-crawls, and contemporary reports spoke of ‘bawdy behaviour, the flinging of beer bottles and raucous singing’.

A motorised charabanc offered little or no protection to the passengers in the event of an overturning accident: they had a high centre of gravity when loaded (and particularly if overloaded), and many had fairly crude and unreliable braking mechanisms. They often travelled the steep and winding roads leading to the coastal villages popular with tourists, and similar roads around the mill towns of Yorkshire and Lancashire. These factors led to fatal accidents like Oxenhope and Blacko, which contributed to their early demise, together with the fact that they were slow and uncomfortable. By the end of the 1920s motorised charabancs were largely superceded by faster, more comfortable and safer motor buses.

Cartoon by Henry Mayo Bateman, from Punch magazine, 1924.

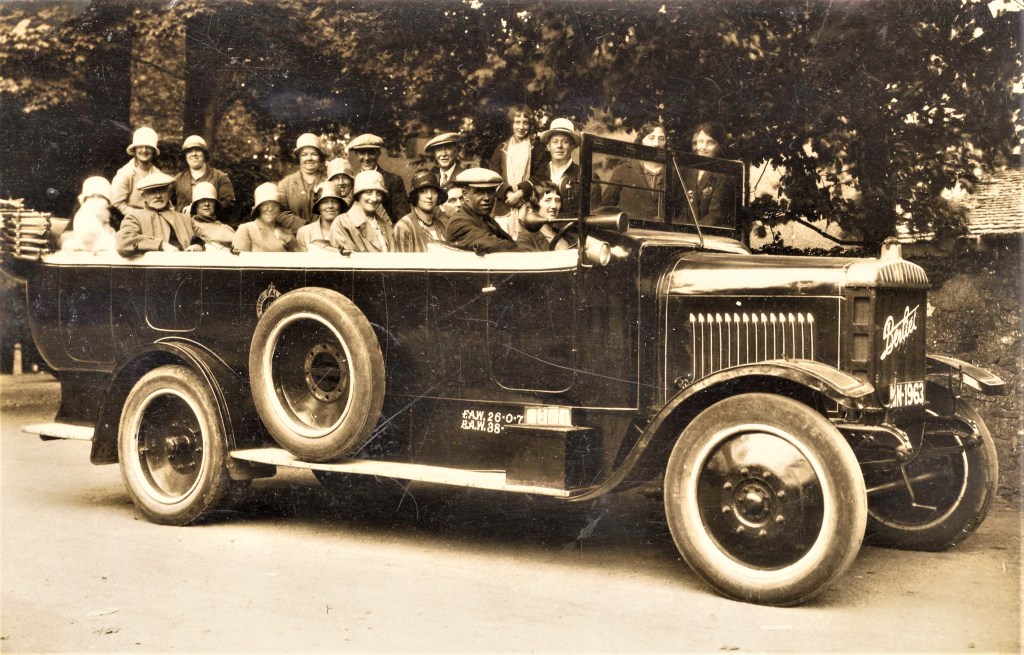

The location and date of this charabanc outing are unknown, but two of the passengers are Sam Foster (c1859-1939), who is buried at Wainsgate, and his daughter Mary Jane Foster (1886-1958).

Thanks to Susan Wilkinson for the photograph.

Thanks to Tim Neal and Keighley & District Local History Society for some of the information on this page.