Lists of the most popular music played at funerals usually include Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’, Robbie Williams’ ‘Angels’, Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’ (played at John F. Kennedy’s funeral) and Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings’ (played at the funerals of Albert Einstein, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Princess Grace of Monaco). Apparently the Match of the Day theme music is a popular choice for the funerals of football fans, Soul Limbo by Booker T. and the MGs is often chosen for cricket fans and The Chain by Fleetwood Mac for Formula 1 fans. Several funeral directors, such as Dignity Funeral Directors and the Funeral Guide website provide suggestions for funeral music. Co-op Funeralcare even publish Top Ten charts of the most popular choices.

There is (or was – their account seems to be currently suspended) also a rather strange American website called Funeral Potatoes, which has ‘the largest searchable database of funeral hymns and memorial songs’: the featured music tends toward the religious rather than secular, but includes songs by, amongst many others, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Dolly Parton, Tom Waits, The Cure, John Lennon, Rihanna, Rod Stewart, Guns N’ Roses, Black Sabbath and The Grateful Dead. The music can be filtered by genre and category, including ‘christian’, ‘catholic’, ‘mormon’, ‘irish’, ‘humorous’, ‘traditional’, ‘punk’ and ‘african’ – although rather disturbingly the ‘african’ selection includes only three songs, all with lyrics in Afrikaans.

Here are some alternatives…..

Click on the LINKS to find out more and listen to the music……..

CLASSICAL

Mozart’s ‘Requiem’ – Handel’s ‘Dead March’ – Chopin’s ‘Marche Funèbre’ – Arvo Pärt’s ‘Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten’

TRADITIONAL

The Parting Glass – Flowers of the Forest

HYMNS & RELIGIOUS SONGS

When the Roll is Called Up Yonder – I Bid You Goodnight – Crossing the Bar (‘Sunset and Evening Star’)

OTHER MUSIC

A few songs about life, death and the like.

CLASSICAL

Arguably the three finest pieces of classical music written for funerals are Mozart’s Requiem, Handel’s ‘Dead March’ and Chopin’s ‘Marche Funèbre’:

REQUIEM in D minor, K.626 (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1791)

A Requiem Mass composed by Mozart in Vienna in 1791, but unfinished at the time of his death at the age of 35 on 5th December that year, it was completed by Mozart’s pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr the following year. It is difficult to determine which parts of the Requiem were written by Mozart and which by Süssmayr, but as Beethoven apparently said: ‘If Mozart did not write the music, then the man who wrote it was a Mozart.’

Portrait of Mozart by Josef Lange

Mozart’s Requiem was played at the re-burial of Napoleon I in 1840 and at the funeral of Frédéric Chopin in 1849. In 2002, on the one-year anniversary of the September 11th attacks, choirs around the world sang Mozart’s Requiem for 24 hours in a global effort to honour those who died.

Part of the Requiem was played by Ted O’Hare on the Wainsgate organ at the funeral service for Eve Clements in 2018.

‘DEAD MARCH’ from SAUL (George Frideric Handel, 1738)

Saul is a dramatic oratorio in three acts written by George Frideric Handel with a libretto by Charles Jennens. Taken from the First Book of Samuel, the story of Saul focuses on the first king of Israel’s relationship with his eventual successor, David. The work includes the famous ‘Dead March‘, a funeral anthem for Saul and his son Jonathan, and some of the composer’s most dramatic choral pieces.

The Dead March was played at the funerals of George Washington, Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington and Winston Churchill. It was also played at Wainsgate at the memorial service for the five people killed in the Oxenhope Charabanc Disaster in 1920, with John William Parker playing the Wainsgate organ.

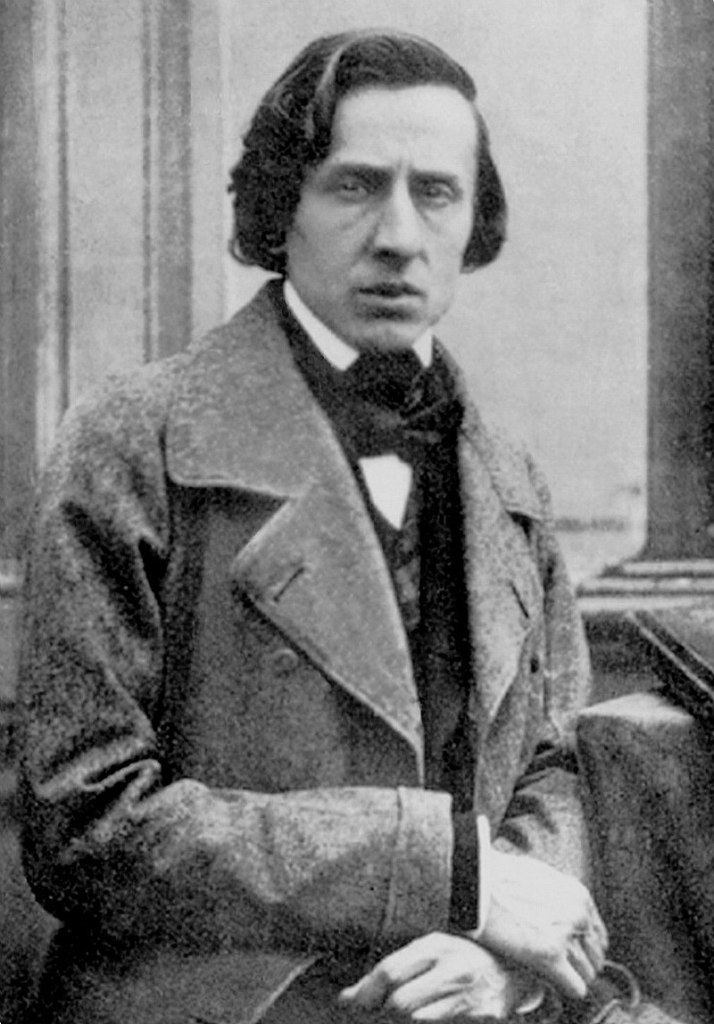

‘MARCHE FUNEBRE’ from PIANO SONATA No.2 (Frédéric Chopin, 1839)

Chopin’s Piano Sonata No.2 was written in Nohant, south of Paris, in 1839, while he was living with his lover, the writer George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin).

The third movement, titled Marche Funèbre, is a ‘stark juxtaposition of funeral march and pastoral trio‘. The composer and pianist Robert Schumann thought that the Marche Funèbre ‘has something repulsive’ about it, while Franz Liszt, a friend of Chopin’s, remarked that the Marche Funèbre is ‘of such penetrating sweetness that we can scarcely deem it of this earth’.

The original manuscript is dated 28th November 1838, the eve of the anniversary of one of the most tragic events in Polish 19th-century history – the November Uprising of 1830 against the Russian Empire.

Chopin died in Paris on the 17th October 1849, aged 39. The cause of death was thought to be tuberculosis, but an examination of his heart in 2014 found that he had suffered from pericarditis, a rare complication of chronic tuberculosis. Chopin on his deathbed had asked for his heart to be removed after his death and returned to Poland, his birthplace (partly from his fear of waking up in his coffin – a condition known as Taphophobia). His heart is now sealed in a pillar at the Church of the Holy Cross, Warsaw. The rest of his body is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

The dying Chopin had planned the music for his funeral, which featured a performance of Mozart’s Requiem. Unknown to him, women were not permitted to sing in the city’s parish churches, and it had taken days of pleading on the part of Chopin’s most powerful friends before a special dispensation was issued by the Archbishop of Paris. The decree allowed female participation provided it remained invisible, and so the women singers were hidden from view behind a black velvet curtain. As the mourners entered the church, the organist played Chopin’s own Marche Funèbre.

The Marche Funèbre has been played at countless funerals around the world: apart from Chopin’s own funeral, it was also performed at the state funerals of John F. Kennedy, Sir Winston Churchill, Margaret Thatcher and Queen Elizabeth II. It has always been a popular choice for the funerals of Soviet and Communist leaders, including Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov, Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin.

* * *

CANTUS IN MEMORIAM BENJAMIN BRITTEN (Arvo Pärt, 1977)

A short canon in A minor, written in 1977 by the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, scored for string orchestra and bell. The work is an early example of Pärt’s tintinnabuli style, which he based on his reactions to early chant music. Its appeal is often ascribed to its relative simplicity; a single melodic motif dominates and it both begins and ends with scored silence.

It was composed as an elegy to mourn the death of Benjamin Britten, a composer who Pärt revered.

Cantus is a meditation on death, but has also been used extensively as background accompaniment in both film and television documentaries. Pärt’s music has also been found to be very popular ‘deathbed music’, helping people feel calm and relaxed as death approaches.

His early works were denounced by Soviet authorities, who disliked his music and his religiosity (he converted to Orthodox Christianity in 1972), and in 1980 he left Estonia with his wife Nora and two sons to live in Austria and then in Germany, returning to live in Estonia in 2010.

TRADITIONAL

THE PARTING GLASS

Possibly the most popular traditional song for funerals is The Parting Glass. A scottish traditional song often sung at the end of a gathering of friends, with versions of the text dating back to 1605: exact lyrics vary between arrangements. The tune today associated with the text is a fiddle tune called ‘The Peacock’ first collected in 1782. It was purportedly the most popular parting song sung in Scotland before Robert Burns wrote ‘Auld Lang Syne’. It has long been sung in Ireland, and one of the most influential of the many recorded versions is the 1959 recording by The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem.

There have been dozens of recorded versions of this song – The Pogues, Sinéad O’Connor, Steeleye Span, Cara Dillon, Rosanne Cash, even Ronan Keating and Ed Sheeran have had a go. This a cappella version by Canadian singers The Wailin’ Jennys is one of the best.

But since it falls unto my lot

That I should rise and you should not

I’ll gently rise and I’ll softly call

Goodnight and joy be with you all

The Parting Glass was sung at the funeral at Wainsgate in 2021 of John Ludlam, by his friends and family gathered at his graveside with glasses of whisky.

FLOWERS OF THE FOREST

Flowers of the Forest is a Scottish folk song commemorating the defeat of the Scottish army, and the death of James IV, at the Battle of Flodden in September 1513. Although the original words are unknown, the melody was recorded around 1620 as “Flowres of the Forrest”, although it might have been composed earlier. Several versions of words have been added to the tune, notably Jean Elliot’s lyrics of 1756, written in Scots, which described the grief of women and children at the loss of over 10,000 men at the Battle of Flodden.

The tune is usually played on the Great Highland Bagpipe. Due to the content of the lyrics and the reverence for the tune, it is a tune that many pipers will perform in public only at funerals or memorial services.

The tune is a simple modal melody: typical of old Scottish tunes it is entirely pentatonic, with the dramatic exception of the 3rd and 5th notes of the second line which are the flattened 7th. There have been numerous recorded versions of the song, including those by Kenneth McKellar, Fairport Convention, Isla St Clair, June Tabor and Mike Oldfield.

The 1935 recording for solo bagpipe featured here is by Pipe Major Forsyth (‘the King’s Piper’).

Solo bagpipe versions of the song are often used at funerals and services of remembrance: many in the Commonwealth know the tune simply as ‘The Lament’ which is played at Remembrance Day ceremonies to commemorate the war dead. It was played at the funerals of Queen Victoria, the Duke of Edinburgh and Sandy Denny, and was played at the memorial service for Queen Elizabeth II.

HYMNS & RELIGIOUS SONGS

WHEN THE ROLL IS CALLED UP YONDER (James Milton Black, 1893)

An 1893 hymn with words and music by James Milton Black, a choir leader and Sunday school teach at a Methodist Episcopal Church in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, it is one of the most popular Christian hymns of all time. The song was inspired by the idea of The Book of Life mentioned in the Book of Revelation, and by the absence of a child in Black’s Sunday school class when the roll was called. The idea of someone not being in attendance in heaven haunted Black, and after visiting the child’s home and calling a doctor to attend her, he went home and wrote the song after not finding one on a similar topic in his hymn collection.

Of the many recorded versions of this hymn (including Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson), this 1997 version by Kelly Joe Phelps is hard to beat.

When the trumpet of the Lord shall sound, and time shall be no more,

and the morning breaks, eternal, bright and fair;

The chosen ones will gather over on the other shore,

and the roll is called up yonder, I’ll be there.

Bessie, the young girl who inspired the hymn, died of pneumonia a few days later, and the song was first sung at her funeral by the young people of the church.

I BID YOU GOODNIGHT / AND WE BID YOU GOODNIGHT / SLEEP ON BELOVED / THE CHRISTIAN’S GOOD NIGHT (Sarah Doudney / Ira D. Sankey, 1884)

Most recordings of the several variants this funeral song credit it as ‘traditional’, but the words are based on a poem entitled The Christian’s Good Night by the English novelist and poet, Sarah Doudney (1841-1926), which was set to music in 1884 by Ira David Sankey (1840-1908) a gospel singer, composer and evangelist from Pennsylvania. The resulting hymn almost immediately became a favourite at funerals, particularly as a ‘lowering down’ hymn.

The song has been adopted and adapted several times: it made its way to the Bahamas and into the repertoire of Joseph Spence and the Pinder family, and was covered by The Incredible String Band on their 1968 album The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. It was recorded by the Grateful Dead in 1969 on the album Live Dead, and was played at the close of most of their live shows until the 1990s. The song re-emerged in 1994 in Yorkshire, when it was recorded under the title Sleep On Beloved on the album Waterson: Carthy (Martin Carthy, Norma Waterson and Eliza Carthy). For more about the background to this song, and to listen to versions of it, click here and here.

This version is from the 1968 Incredible String Band recording, which is based on the Joseph Spence / Pinder family version recorded in 1964 on the LP The Real Bahamas in Music and Song.

Lay down my dear sister, won’t you lay and take your rest

Won’t you lay your head upon your saviour’s breast

And I love you, but Jesus loves you the best

And I bid you goodnight, goodnight, goodnight.

This song was sung at the funeral of the highly influential English Particular Baptist Preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892), known by many as ‘The Prince of Preachers’ and the author of sermons, an autobiography, commentaries, books on prayer, devotionals, magazines, poetry, and hymns. He died in France, and was buried at West Norwood Cemetery. An estimated 100,000 people either passed by Spurgeon as he lay in state in the Metropolitan Tabernacle or attended the funeral services (four memorial services were held prior to the funeral).

Charles Spurgeon was vehemently opposed to slavery: he lost support from the Southern Baptists, sales of his sermons dropped, and he received scores of threatening and insulting letters as a consequence. In a letter to the Christian Watchman and Reflector in Boston, he declared:

I do from my inmost soul detest slavery… and although I commune at the Lord’s table with men of all creeds, yet with a slave-holder I have no fellowship of any sort or kind. Whenever [a slave-holder] has called upon me, I have considered it my duty to express my detestation of his wickedness, and I would as soon think of receiving a murderer into my church… as a man stealer.

CROSSING THE BAR (‘SUNSET AND EVENING STAR’)

Crossing the Bar is an 1889 poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson. It is thought that Tennyson wrote it as an elegy ( in English literature usually a lament for the dead): the narrator uses an extended metaphor to compare death with crossing the ‘sandbar’ between the river of life, with its outgoing ‘flood’, and the ocean that lies beyond death, the ‘boundless deep’, to which we return.

Tennyson’s words have been set to music by many people, including Hubert Parry, Joseph Barnby, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Charles Ives and John Philip Sousa. In 2012 the poem was set to music by American musician Rani Arbo, with a subsequent choral arrangement by Peter Amidon.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Crossing the Bar was sung at Wainsgate at the memorial service for the five people killed in the Oxenhope Charabanc Disaster in 1920, with the Wainsgate choir conducted by A. R. Ashworth.

OTHER MUSIC

Here are a few more tunes that could perhaps be played at funerals, but seldom are. Some are religious in nature, some view matters from an agnostic or atheist viewpoint. All of them reflect on the meaning of life and the mystery of death, but they are by no means all sad or gloomy: some could be considered irreverent, some are life-affirming and uplifting, some are moving, some are even quite cheerful.

O DEATH – Ralph Stanley, 2000 (Traditional / Lloyd Chandler)

I’ll close your eyes so you can’t see

This very hour, come and go with me

I’m death I come to take the soul

Leave the body and leave it cold

O Death is a traditional Appalachian folk song, listed as number 4933 in the Roud Folk Song Index. The song is generally attributed to the musician and Baptist preacher Lloyd Chandler, but was probably taken or adapted from folk songs already existing in the region. This a cappella version of the song was recorded for the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Ralph Stanley (also known as Dr. Ralph Stanley) was a bluegrass musician from Southwest Virginia, and was a Primitive Baptist Universalist, a denomination that split from other Primitive Baptists in 1924. Christian universalists believe that ‘all human beings will ultimately be saved and restored to a right relationship with God’. Their congregations are located mainly in the central Appalachian region, and they are popularly known as ‘No-Hellers’ due to their belief that there is no Hell as such, but that Hell is actually experienced in this life.

Ralph Stanley was also a Freemason and a Shriner (a member of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine), and it would appear that the beliefs of Freemasonry and Christian universalism are quite compatible. His 2016 funeral service, which includes the Masonic rite, was recorded and can be viewed on YouTube.

WE SING HALLELUJAH – Richard and Linda Thompson, 1974 (Richard Thompson)

A man is like a rusty wheel

On a rusty cart

He sings his song as he rattles along

And then he falls apart

Richard Thompson was brought up a Presbyterian but converted to Sufism (a mystical-ascetical movement within Islam) in his twenties. He remains a committed Muslim.

This cheerful little song was, like The Parting Glass, played at John Ludlam‘s funeral in 2021.

YOUR LONG JOURNEY – Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, 2007 (Rosa Lee Watson and Arthel Lane ‘Doc’ Watson)

Oh, my darling

My darling

My heart breaks as you take your long journey

The sleeve notes for Raising Sand incorrectly credit the song as ‘Traditional, arranged by Arthur Lane Watson and Rosalie Watson’. The song was written by Rosa Lee Watson with assistance from her husband, Arthel Lane ‘Doc’ Watson, the legendary guitarist, singer and songwriter. It is not known as a traditional song, although the Watsons may have heard a similar song by Frank Hutchison. The song was also originally titled Your Lone Journey.

DIRT IN THE GROUND – Tom Waits, 1992 (Tom Waits & Kathleen Brennan)

.…. hell is boiling over and heaven is full

We’re chained to the world and we all gotta pull

And we’re all gonna be just dirt in the ground

You can always rely on Tom Waits to look on the bright side of things.

LET THE MYSTERY BE – Iris DeMent, 1992 (Iris DeMent)

Some say once you’re gone you’re gone forever

And some say you’re gonna come back

Some say you rest in the arms of the Saviour

If in sinful ways you lack

Iris Dement was born in Paragould, Arkansas in 1961, the youngest of fourteen children in the family. She was brought up in the Pentacostal church, but left as a teenager. Let the Mystery Be has been described as a ‘spritely agnostic anthem’.

‘It was full gospel-fundamentalist, I guess you’d call it. There was hell and there was heaven, and the in-between was just kind of preparation to get to the better place. In everyday life, your primary focus was staying out of the bottom side of the afterlife’.

10 MILES TO GO ON A 9 MILE ROAD – Jim White, 2001 (Jim White)

American musician Jim White was ‘saved’ as a youth by the Assembly of God Pentecostal Church in Pensacola, Florida, but left after a couple of years, and his music reflects the paradox he perceives as inherent in religious faith. His first album was called (The Mysterious Tale of How I Shouted) Wrong-Eyed Jesus! and his songs have included When Jesus Gets a Brand New Name and If Jesus Drove a Motor Home.

Sometimes you throw yourself into the sea of faith,

And the sharks of doubt come and they devour you.

Other times you throw yourself into the sea of faith

Only to find the treasure lost in the shipwreck inside of you!

BLACK MUDDY RIVER – Norma Waterson, 1996 (Jerry Garcia & Robert Hunter)

When it seems like the night will last forever

And there’s nothing left to do but count the years

When the strings of my heart start to sever

And stones fall from my eyes instead of tears

I will walk alone by the black muddy river

And dream me a dream of my own

This was the last song sung by Jerry Garcia at what was to be the Grateful Dead’s final concert on 9th July 1995 at Soldier Field, Chicago. The band were exhausted and well past their best, and Garcia was in poor health. Black Muddy River was the first song of the encore, followed by Box of Rain, a song written for Phil Lesh’s dying father. Jerry Garcia died exactly a month later, aged 53, at a rehabilitation clinic in California.

RIBBONS AND BOWS – Hannah Sanders & Ben Savage, 2016 (Richie Stearns)

If I could choose the way that I was to die

I’d go falling, through the hot summer sky

Ribbons and bows tied to my hands and my feet

I’d gaze across the world and I’d feel complete

I first heard this song played by Hannah Sanders and Ben Savage at Wadsworth Community Centre in Old Town. It was written by American banjo player Richie Stearns, and although it sounds like a cheerful little tune, the lyrics hint at something darker.

LIFE’LL KILL YA – Warren Zevon, 2000 (Warren Zevon)

From the President of the United States

To the lowliest rock and roll star

The doctor is in and he’ll see you now

He don’t care who you are

DON’T LET US GET SICK – Warren Zevon, 2000 (Warren Zevon)

Don’t let us get sick

Don’t let us get old

Don’t let us get stupid, all right?

Just make us be brave

And make us play nice

And let us be together tonight

Born in Chicago in 1947, Warren Zevon’s father was a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine, a bookie who worked for the Los Angeles mobster Meyer ‘Mickey’ Cohen. His mother was from a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon) family and of English descent.

Zevon had a lifelong phobia of doctors and said he seldom consulted one. In 2002 he was diagnosed with pleural mesothelioma, a cancer usually caused by exposure to asbestos, and given three months to live. It is thought that he was exposed to asbestos as a child, playing in the storeroom of his father’s carpet shop. Refusing treatments he believed might incapacitate him, Zevon instead began recording his final album, The Wind, which was released on 26th August 2003. He died less than two weeks later, aged 56, and his ashes were scattered in the Pacific Ocean.

When asked if he knew something more about life and death after his terminal diagnosis, he offered these words of wisdom:

‘ENJOY EVERY SANDWICH’

IS THAT ALL THERE IS? – Peggy Lee, 1969 (Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller)

If that’s all there is my friends, then let’s keep dancing

Let’s break out the booze and have a ball

If that’s all there is

This song was inspired by the 1896 story ‘Disillusionment’ by Thomas Mann (Jerry Leiber’s wife, born Gabrielle Rosenberg in Germany, escaped ahead of the Nazis, settled in Hollywood and introduced Leiber to the works of Thomas Mann), and the music recalls the style of Kurt Weill.

In 1992, film director Lindsay Anderson scattered the ashes of British actresses Rachel Roberts and her friend Jill Bennett, both of whom took their own lives, on the Thames during a boat trip. The ashes-scattering is the closing segment in Anderson’s final film, an autobiographical BBC documentary titled ‘Is That All There Is?’. As friends and colleagues of the actresses raise their glasses in a toast and toss flowers into the Thames, Alan Price, accompanying himself on keyboard, sings ‘Is That All There Is?’.

* * *

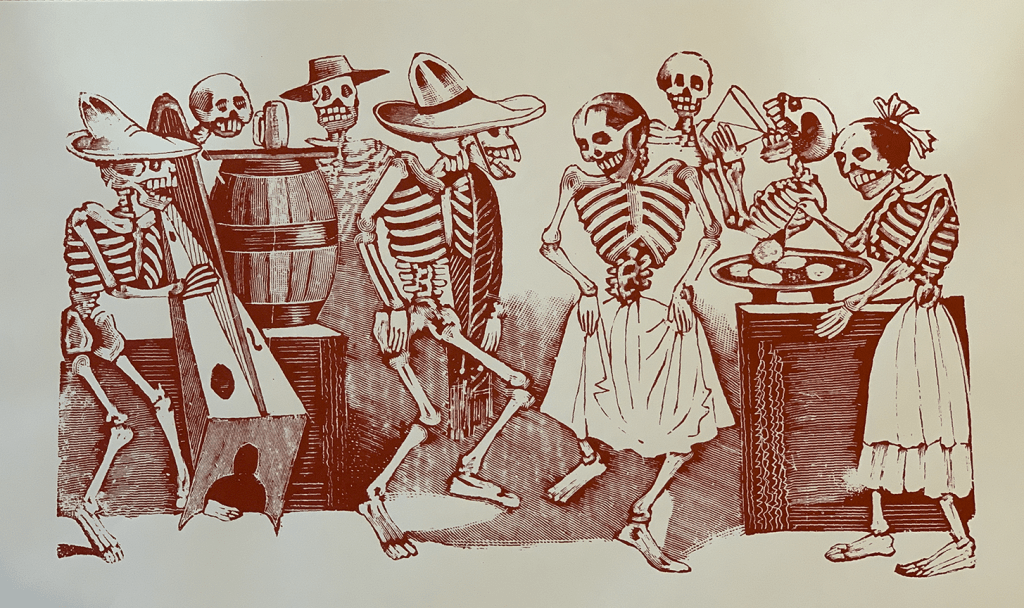

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar (1852–1913) was a Mexican lithographer, engraver and cartoonist, best known for his calavera images (calavera literally translates as skull, but has come to mean the entire skeleton). Posada is generally credited with popularizing the calavera images associated with the Day of the Dead in Mexico, and his most iconic image is a calavera image wearing a hat decorated with flowers. She appeared originally as ‘la Garbancera’ and was later named ‘la Calavera Catrina‘ by Diego Rivera. ‘La Catrina’ as she is now known, is believed to have first appeared in 1912, just a few months before Posada’s death.

He was arguably the most popular and influential of all Mexican artists, but never achieved the same level of recognition as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Largely forgotten by the end of his life, José Guadalupe Posada died in 1913 of ‘acute alcoholic enteritis’, caused by years of heavy drinking. He reportedly died penniless and was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the Dolores Cemetery, Mexico City.