Keep Death & Judgement always in your eye;

None are fit to live who are not fit to die;

Make use of present time, because you must

Take up your lodging shortly in the dust

‘Tis dreadful to behold the setting sun,

And night approaching, e’er your work is done.

An epitaph in St.Philip’s churchyard, Birmingham, 1835. From An Original Collection of Extant Epitaphs, gathered by a Commercial in spare moments by Frederick Maiben (1870)

* * *

Click on the LINKS to find out more…..

EPITAPHS

MODERN EPITAPHS

BIBLICAL EPITAPHS

From Genesis to Revelation.

HYMNS & DEVOTIONAL POEMS

Words from the works of Isaac Watts, John Wesley, Charles Wesley and others.

OTHER EPITAPHS

Some original, some also found in other graveyards.

LITERARY EPITAPHS

Epitaphs on Wainsgate memorials taken from the works of T.S.Eliot, Samuel Beckett, William Wordsworth, J.R.R.Tolkien, Mervyn Peake, A.E.Housman & Victor Hugo.

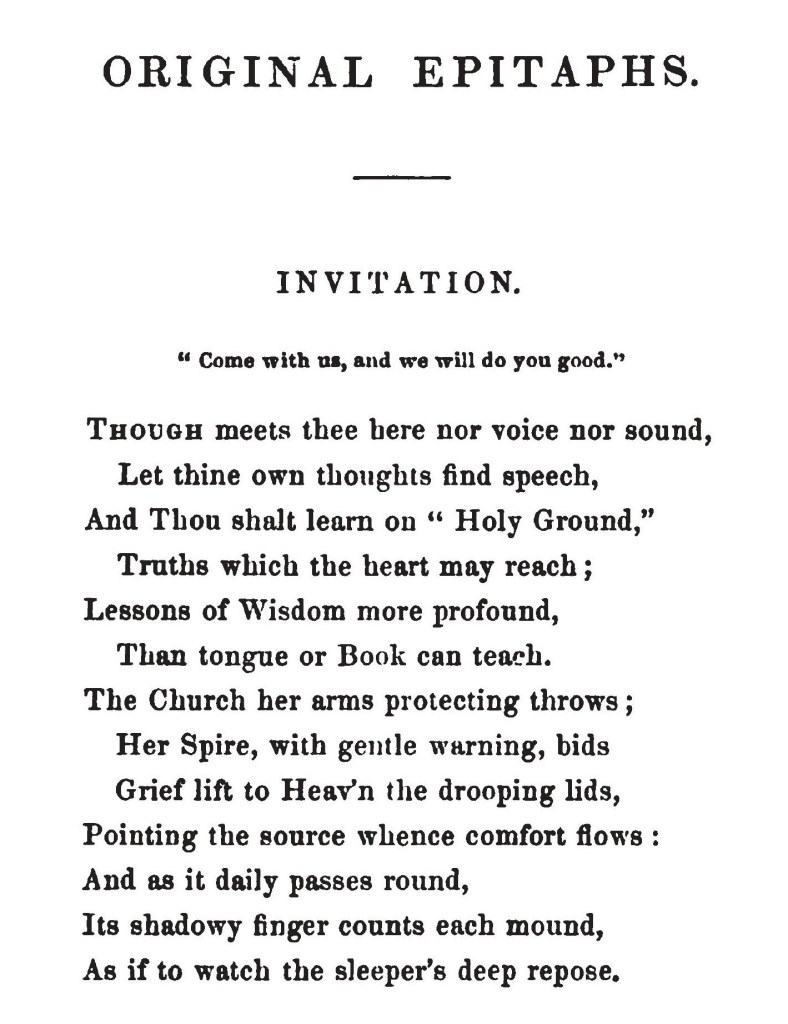

The CHURCHYARD MANUAL & LYRA MEMORIALIS

Two nineteenth century collections of suggested epitaphs.

An ORIGINAL COLLECTION of EXTANT EPITAPHS…

‘.….gathered by a Commercial in spare moments’. Published by Frederick Maiben in 1870.

* * *

EPITAPHS

epitaph (noun): a phrase or form of words written in memory of a person who has died, especially as an inscription on a tombstone.

From Lyra Memorialis – Original Epitaphs and Churchyard Thoughts in Verse by Joseph Snow (1847)

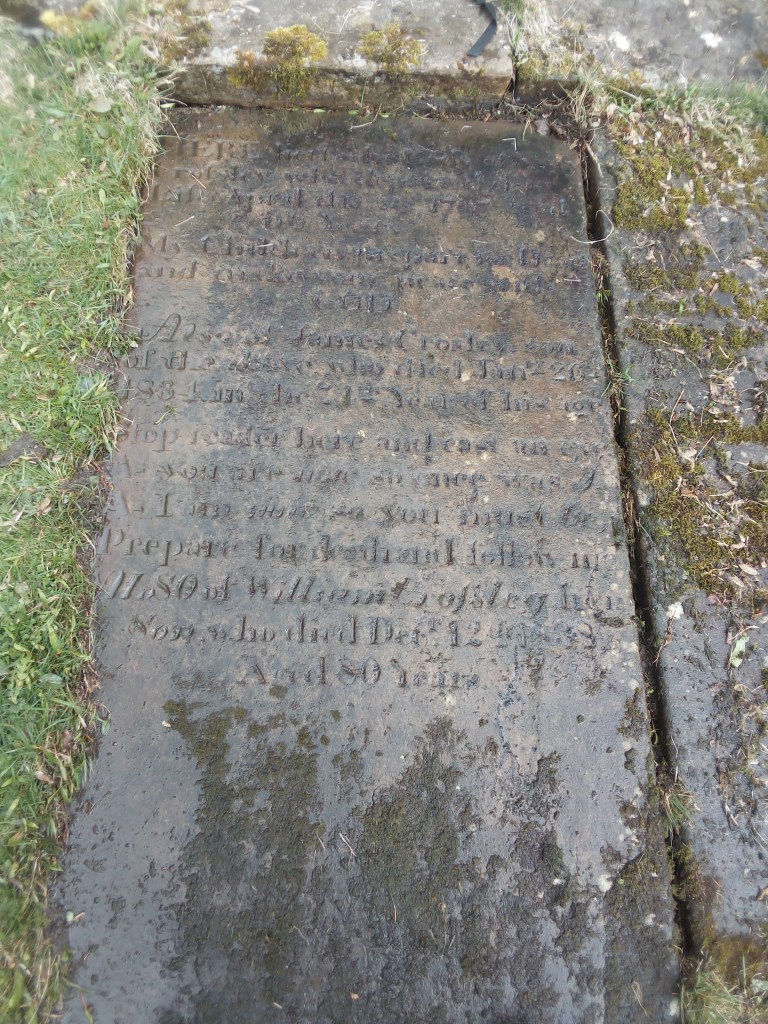

Remember me as you pass by

As you are now so once was I

As I am now so must you be

Prepare in time to follow me

One of the most common epitaphs – most British graveyards have at least one example of this verse or one of the many variations of it. Examples are found dating from the Middle Ages to the late 19th century – this one is from Howden Minster near York and dates from 1770.

This epitaph is meant as a warning of the inevitability of death, and early examples were often accompanied by graphic representations of skulls, skeletons or cadavers. The verse must have been part of popular oral culture, handed down from one generation to the next, and is thought to have a pagan origin.

The essence of the epitaph can be rendered in four words in Latin – Hodie Mihi, Cras Tibi – today it is me, tomorrow it will be you.

There is an example of this epitaph at Wainsgate on one of the earliest gravestones – a flat slab (without skulls, skeletons or similar embellishments) dating from the late 1700s (the date of the earliest burial is unclear). The grave (OY53) is that of Mary Crossley and her sons James (who died in 1834 aged 73) and William (who died in 1838 aged 80).

Stop reader here and cast an eye

As you are now so once was I

As I am now so you must be

Prepare for death and follow me

Another epitaph warning us of the inevitability of death (and the fact that it often surprises us when we were least expecting it) is this headstone (CY280) commemorating the Bloomer family from Foster Clough – Grace Bloomer, who died in 1852, her husband Samuel, who died in 1867 and two sons. John Bloomer, who died in 1865 aged 24 and James Bloomer, who died in 1898 and is believed to have been the landlord of the Shoulder of Mutton Inn in Midgley.

All you that look on my tomb

Oh think how quickly I was gone

Death does not always warning give

Therefore be careful how you live.

* * *

Most of the inscriptions on the gravestones and memorials at Wainsgate are simple and to the point: ‘In memory of…..’, ‘In loving memory of…..’, ‘In affectionate remembrance of…….’, followed by names, date of death (and sometimes dates of birth) and ages.

Most people are recorded as having ‘died‘, or sometimes ‘departed this life‘ rather than ‘passed away‘ or ‘fell asleep‘.

Only three inscriptions are in Latin:

‘Ante adventum iptius mali tolitur’ (He was taken away from the evil to come) – from the gravestone (OY124) of Stephen Fawcett, son of John Fawcett, who died of smallpox in 1774 aged four. The quotation is based on Isaiah 57:1.

‘Amidus usque ad aras, amata bene’ (A friend to the very end, well loved) – from the gravestone (F739) of George and Elizabeth Hodgkinson and their son Joseph, who died in 1911 aged 17.

‘Memoria justi est beata’ (The memory of the righteous is blessed) – from the gravestone (A402) of Thomas and Betty Pickles and their son William. The inscription comes after the name of Betty, who died in 1857 aged 68.

Sometimes the inscription mentions where a person lived or died: some mention their relationship to other family members: ‘beloved wife of…..’, ‘dearly loved husband of…..’.

Many of the older gravestones do not name babies and young children (even though they might be named in the burial register or death certificate), particularly when families may have lost several infants: ‘…..also of four of their infants’, ‘…..also of 5 children who died in infancy’.

* * *

A few phrases are common on gravestones and memorials everywhere, and these examples appear more than once on gravestones at Wainsgate:

Rest in Peace

Often abbreviated to R.I.P – from the Latin requiescat in pace. First found on tombstones some time before the fifth century.

At Rest

Fairly self-explanatory.

Thy Will Be Done

From the third of the seven petitions in the Lord’s prayer:

Thy will be done on earth as it is in Heaven.

Until the Day Break and the Shadows Flee Away

From Song of Solomon 4:6 –

Until the day break, and the shadows flee away, I will get me to the mountain of myrrh, and to the hill of frankincense.

also Song of Solomon 2:17 –

Until the day break, and the shadows flee away, turn, my beloved, and be thou like a roe or a young hart upon the mountains of Bether.

In the Midst of Life We Are in Death

From the committal in the service for the burial of the dead in the Book of Common Prayer. The phrase is a translation by Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer of the Gregorian chant Media vita in morte sumus.

Man that is born of a woman hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow, and never continueth in one stay.

In the midst of life we are in death: of whom may we seek for succour, but of thee, O Lord, who for our sins art justly displeased?

Peace, Perfect Peace

From the hymn Peace, Perfect Peace, in this Dark World of Sin?, written in 1875 by Edward Henry Bickersteth at the bedside of a dying relative. Of the dozens of hymns he wrote, this one became the most popular, and is still a popular choice for Christian funerals. The phrase is taken from Isaiah 26:3 –

Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace, whose mind is stayed on thee: because he trusteth in thee.

Resting Where No Shadows Fall

Found on gravestones in this country, in the USA, Australia and other countries. It is found on many Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones around the world, particularly on a number of the memorial stones at Kanchanaburi War Cemetery (known locally as the Don-Rak War Cemetery) in Thailand, the main cemetery for prisoners of war (mainly British, Australian and Dutch) who died building the Burma Railway.

It appears on most lists of suggested epitaphs published by funeral directors and memorial masons around the world.

Where No Shadows Fall is the title of a 2015 novel by Scottish crime writer Peter Ritchie, and Resting Where No Shadows Fall is the title a 2016 album by British metal band This Dying Hour.

But where does this phrase come from? There is nothing in the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, any well known hymns, poems or other texts that matches the wording.

The only conceivably plausible explanation that I have found is that it is from a translation of a Danish hymn, Naar min Tunge ikke mere, which is found in The People’s Hymnal of 1867, and contains the line ‘Home where no shadows fall’. It would appear that this is not an accurate translation of the original Danish text, and was created to rhyme with the following line – ‘Home to the Monarch’s Hall’.

If anyone knows of a better explanation of the origin of this very common epitaph, please let me know.

Gone but Not Forgotten

‘They say that we all die twice – when our last breath leaves our body, and when our name is spoken for the last time’.

This quote, or variations of it, have been attributed to (amongst others), Ernest Hemingway, existential psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom, rapper Macklemore and the artist Banksy. The origins of the idea are undoubtably a lot older, possibly originating in Ancient Egypt, possibly in Africa, and echoed in the Mexican Día de los Muertos and the Jewish tradition of Yahrzeit.

In the 2009 book Sum by neuroscientist David Eagleman there is a short story titled Metamorphosis, in which the author suggests that there are three deaths, and that we wait in a celestial lobby in a state of limbo until our third death, when the time comes for us to go to our final destination:

‘There are three deaths. The first when the body ceases to function. The second is when the body is consigned to the grave. The third is that moment, sometime in the future, when your name is spoken for the last time.

So you wait in this lobby until the third death….. Tragically, many people leave just as their loved ones arrive, since the loved ones were the only ones doing the remembering.

And that is the curse of this room: since we live in the heads of those who remember us, we lose control of our lives and become who they want us to be.’

Gone Before

A phrase which is not from the Bible or any other religious work, but was first used by the Greek playwright Aristophanes (c446-c386 BCE):

Your lost friends are not dead, but gone before, advanced a stage or two upon that road which you must travel in the steps they trod.

In Jesus Keeping

Another epitaph taken from the hymn Peace, Perfect Peace, in this Dark World of Sin?, written in 1875 by Edward Henry Bickersteth. The number of verses and their wording seems to vary, but this verse appears in most publications of the hymn:

Peace, perfect peace, with loved ones far away?

In Jesus’ keeping we are safe, and they.

Asleep in Jesus

A popular epitaph, assumed to be taken from the hymn Asleep in Jesus! blessed sleep, written in 1832 by Margaret Mackay.

Asleep in Jesus! Far from thee

Thy kindred and their graves may be;

But there is still a blessèd sleep,

From which none ever wakes to weep.

It seems that Mackay was inspired by an epitaph (‘Sleeping in Jesus’) on a gravestone in Pennycross, Devon, which in turn may well have been inspired by 1 Thessalonians 4:14 –

For if we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so them also which sleep in Jesus will God bring with him.

Blessed are the Dead who Die in the Lord

From Revelation 14:13, and also the title of a hymn by Isaac Watts.

And I heard a voice from heaven saying unto me, Write, Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord from henceforth: Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours; and their works do follow them.

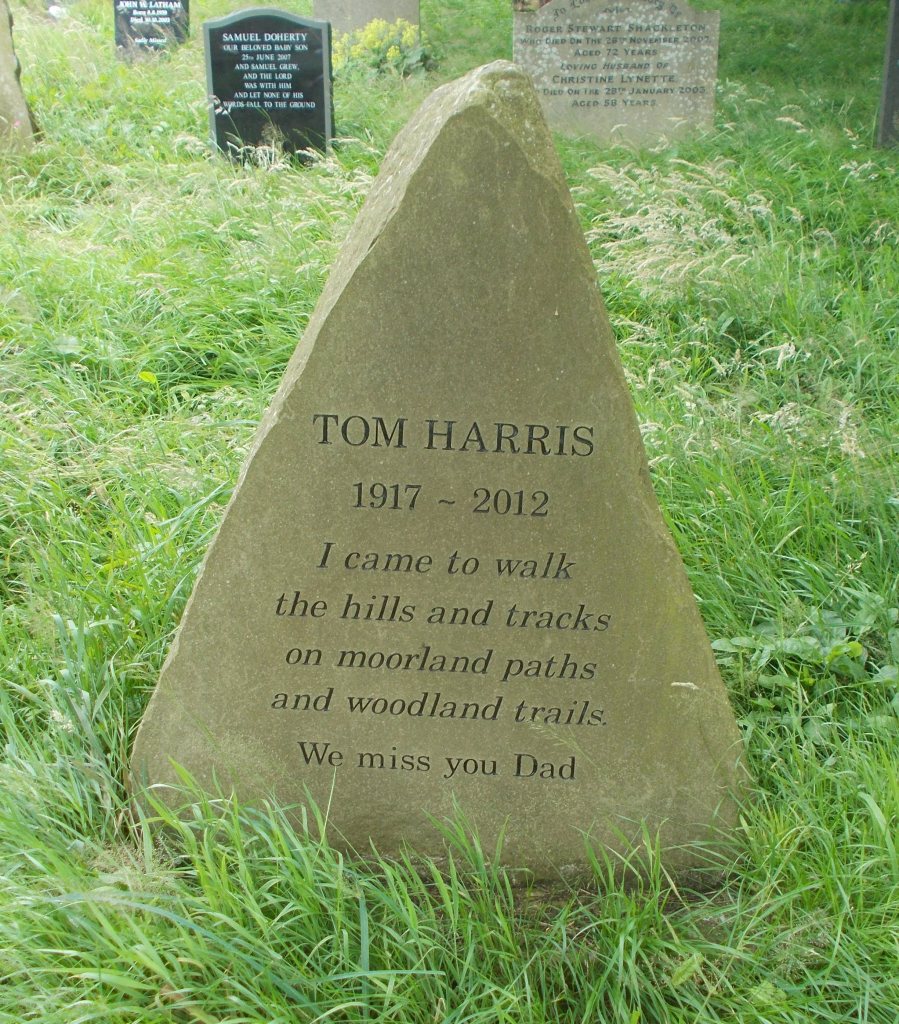

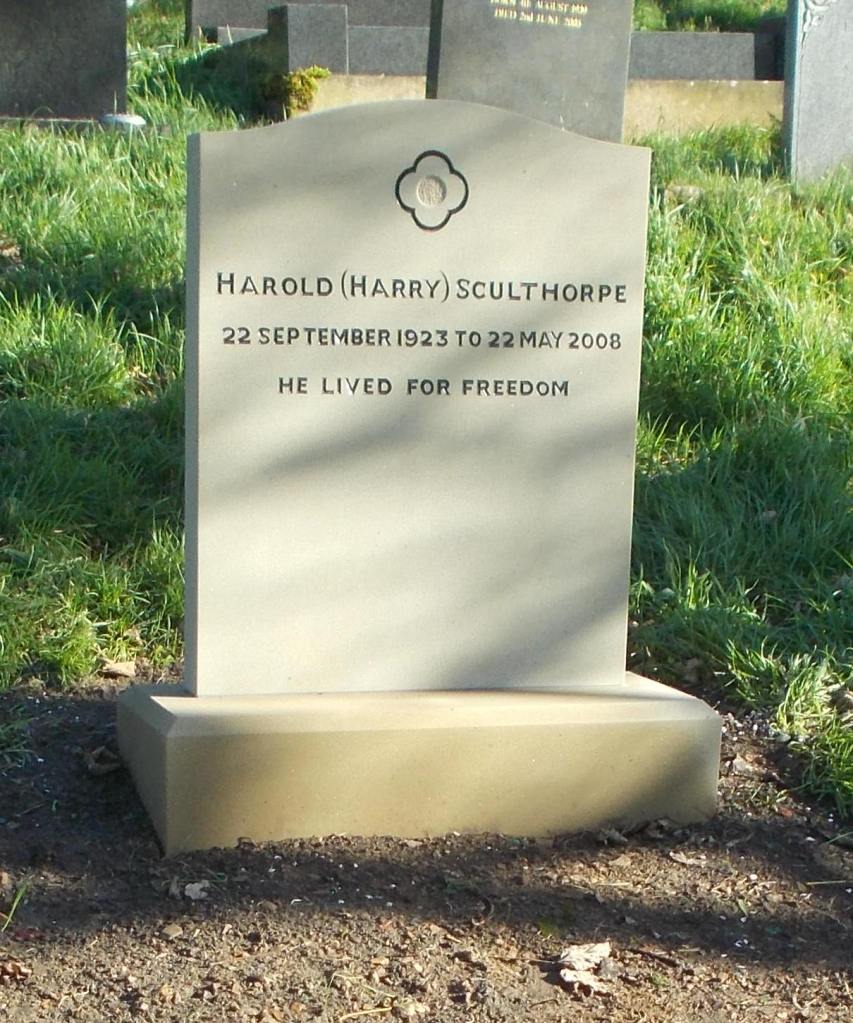

MODERN EPITAPHS

Many of the more recent headstones have epitaphs which are less formal, less religious and more personal – the headstones shown below date from 1997. To find out more about some of the people commemorated, click on the caption links.

Some more examples of modern epitaphs can be found here and here.

(1969-2022) – H1057

(1933-1997) – I920

(1937-2021) – H1056

(1947-2000) – I997

(1964-2015) – H1031

(1917-2012) – H1029

(1923-2008) – H1024

(1957-2019) – D1043

(1948-2011) – H1028

(1950-2004) – I975

(1944-2017) – D1036

(1953-2020) – I923A

BIBLICAL EPITAPHS

What man is he that liveth, and shall not see death? shall he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave?

Psalms 89:48

….. for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.

Genesis 3:19

Some of the Baptist ministers buried or commemorated at Wainsgate (Richard Smith, John Crook, John Bamber, James Jack, Arnold Bingham) have quotations from the Bible on their gravestones. Other biblical epitaphs found at Wainsgate include:

Thomas Haigh, his wife Sarah (born Bancroft) and their son Harry were all closely associated with the Sunday School at Wainsgate, and unsurprisingly the epitaphs on their headstone (B264a) are all from the Bible:

‘I have loved the habitation of thy house, and the place where thine honour dwelleth’.

‘He that followeth me shall have the light of life’.

‘In as much as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me’.

The quotations are from Psalms 26:8, John 8:12 and Matthew 25:40.

The headstone also mentions ‘an infant’ – Richard Henry Haigh, who was buried on 27th March 1899 aged one month.

‘By sorrow of heart, the spirit is broken’.

Found on the headstone (B181a) commemorating James and Elizabeth Sutcliffe, their son Arthur, who died in 1880 aged 2, their daughters Ada Sutcliffe and Emily Grave and son-in-law Norris Grave. James Sutcliffe died in 1888 aged 36.

The epitaph is taken from Proverbs 15:13 –

‘A merry heart maketh a cheerful countenance: but by sorrow of the heart the spirit is broken’.

‘Be ye also ready: for in such an hour as ye think not the Son of man cometh’.

(Matthew 24:44) From the headstone (A409) of the Barrett family of Mill House, Midgley – Ann, who died in 1860 aged 45, her husband William, who died in 1865 aged 50, and their son Isaac, who died in 1872 aged 19. The headstone also mentions ‘an infant’ – Rebecca, who died in 1856, aged 3.

The name is spelt Barrett in most records, but on the headstone is spelt either Barritt or Barrit.

‘I say unto you watch for in such an hour as ye think not

the SON OF MAN cometh.’

A similar epitaph, based on Matthew 24:44, on the headstone (B78a) of Thomas Feather of Foster Mill Lane, who died in 1879 aged 40 years.

‘Blessed are the pure in heart; for they shall see God.’

‘Jesus said unto her I am the resurrection and the life’.

These two verses, Matthew 5:8 and part of John 11:25 (which continues ‘he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.’) are both on the headstone (A429) commemorating two sons (Thomas and John), two daughters (Esther and Ann) and a grandaughter (Mary Cockcroft) of the late James & Mary Moss of Machpelah.

‘Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city.’

Revelation 22:14 – From the headstone (FY186) commemorating Joseph Pickles and Hannah Pickles (born Shackleton) of Lane Ends, Midgley, four sons and a daughter: Benjamin died in 1835 aged 7 months, Elizabeth in 1838 aged 2, Joseph in 1851 aged 17 and Roger in 1867 aged 34.

Their eldest son John died in America in 1886, aged 58.

The inscription on the chest tomb (FY203) of James Heap, late of Goodshaw Hill, Haslingden, and his sister Elizabeth Heap is from Psalms 116:15 –

‘Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints’.

James died in 1824 aged 71 and Elizabeth died in 1836, aged 80 or 81, Both died at Ewood Hall.

‘For so he giveth his beloved sleep’

From Psalm 127:2. The complete verse (KJV) reads:

‘It is vain for you to rise up early, to sit up late, to eat the bread of sorrows: for so he giveth his beloved sleep’.

The word ‘vain’ in this context means futile, empty or worthless.

The headstone (B319a) commemorates Jane Wadsworth of Far Nook, her daughter Mary Jane and Mary Jane’s first husband (and her first cousin), Fred Wadsworth.

Fred Wadsworth died in Storthes Hall Asylum in 1915, aged 46.

The headstone (A446) commemorating William Greenwood of Latham, his wife Jane, son Ebenezer and an unnamed infant has two quotations from the Bible and two lines from a hymn:

‘What thou knowest not now, thou shalt know hereafter’.

This is rather badly transcribed from John 13:7, which reads ‘Jesus answered and said unto him, What I do thou knowest not now; but thou shalt know hereafter.’ The other quotation from the Bible is from Psalms 26:8 –

‘Lord, I have loved the habitation of thy house, and the place where thine honour dwelleth’.

‘No more exposed to burning skies,

Or winter’s piercing cold.’

The other epitaph on this headstone is taken from a hymn by Joseph Swain (1761-1796) that is found in many Baptist hymnals of the time. Swain was a Baptist minister, poet and hymn writer, originally from Birmingham and later pastor of East Street Baptist church in Walworth. He is buried in Bunhill Fields, London.

HYMNS & DEVOTIONAL POEMS

The inscription on this flat gravestone (OY91) which is outside the chapel doors, is badly worn and parts of it are hard to read. The gravestone commemorates Sally Tatham, who died in 1817, and her husband John who died in 1851 aged 86. The epitaph appears to be the first verse of the hymn Hark! from the tombs a doleful sound by Isaac Watts:

‘Hark! from the tombs a doleful sound

My ears attend the cry:

Ye living men! come view the ground

Where you must shortly lie’

Isaac Watts (1674-1748), was a Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician, sometimes referred to as the ‘Godfather of English Hymnody’. Born in Southampton, Watts was said to have started studying Latin before at the age of four, but was unable to attend Oxford or Cambridge because of his nonconformist beliefs, and was educated at Rev. Thomas Rowe’s Dissenting Academy in Stoke Newington. He is buried in Bunhill Fields, and is commemorated with a statue in Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington.

Verses from hymns, psalms and devotional poems by Watts are often used as epitaphs in Britain and America. Among the many hymns he wrote (at least eight hundred are known to have been published) are Joy to the World, When I Survey the Wondrous Cross and Our God, Our Help in Ages Past.

‘Jesus can make a dying bed

Feel soft as downy pillows are

While on his breast I lean my head

And breathe my life out sweetly there’.

From the headstone (FY141) commemmorating John Pickles of Great House in Stansfield, who died in 1867 aged 16. His parents, Thomas Pickles who died in 1877 aged 61 and Mary Pickles who died in 1882 aged 77 are buried with him. The words are from Hymn 31 by Isaac Watts.

‘Why do we mourn departing friends

Or shake at death’s alarms?

’Tis but the voice which Jesus sends

To call them to His arms’.

From the gravestone (FY210) of Ann and William Bancroft of Chisley Hall. Ann died in 1833 aged 61 and William died in 1848 aged 77. The words are again from a hymn by Isaac Watts, The Death and Burial of a Saint.

‘They die in Jesus, and are blest;

How calm their slumbers are!

From sufferings & from sins released,

And freed from every snare’.

The headstone commemorates James Greenwood and his wife Hannah of Black Hill, and their daughter Eliza who died in 1846 aged 7 weeks. Also buried in the plot (CY319) but not recorded on the headstone is an unnamed infant, probably a grandchild, who died in 1863 aged 11 days.

The words are from the hymn by Isaac Watts Blessed Are the Dead that Die in the Lord.

‘Nothing on earth do I desire

But thy pure love within my breast;

This, only this, will I require,

And freely give up all the rest’.

This epitaph appears on two memorials at Wainsgate: shown here is the gravestone (CY349) of Joseph and Hannah Sutcliffe of Old Laithe, their daughter Betty Sutcliffe who died in 1849 aged 29, and their son Amos who died in 1884 aged 63.

The other (CY315) is the grave of Sally Greenwood, who died in 1846 aged 37, her husband Robert who died in 1859 aged 52 and two of their daughters: Sarah who died in 1857 aged 20 and Elizabeth who died in 1859 (two days before her father) aged 16. Interestingly, the burial register gives different ages to those shown on the gravestone for all except Elizabeth.

The epitaph is from the hymn Come, Saviour, Jesus, From Above, (Venez Jésus, mon salutaire), written by Antoinette Bourignon (1616-1680) and translated by John Wesley (1703-1791). Antoinette Bourignon was a French-Flemish mystic, who believed that she was chosen by God to restore true Christianity on earth and became the central figure of a spiritual network that extended throughout the Netherlands, France, England, and most especially Scotland. John Wesley was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist, and founder, with his brother Charles, of the Methodist movement in the Church of England.

The epitaph for Sarah Greaves of Hebden Bridge, who died in 1860 aged 48. The headstone (A500/501) also commemorates six members of her family: her brothers William and Robert Greaves, Edward Greaves and his wife Mary, and Joshua Greaves and his wife Hannah, both of Whitworth in Lancashire.

‘Thy day has come, not gone:

Thy sun has risen, not set:

Thy life is now beyond

The reach of death or change:

Not ended, but begun.’

The author of this epitaph is probably Horatius Bonar (1808-1889), the Scottish preacher, poet and hymnodist. It appears in a verse of the hymn Gone Before in the collection Hymns of Faith and Hope.

These words, usually followed by the line: ‘O noble soul! O gentle heart! Hail and farewell’ appear in several memorial addresses of 19th century American politicians and Freemasons.

‘My Father’s hand prepares the cup

And what He wills is best’

William Crabtree of Commercial Street, Hebden Bridge, died in 1912 aged 58. His widow Mary Hannah married Matthew Adams in 1915, and is buried with her first husband in plot C602.

The epitaph is from the hymn Away, My Needless Fears, one of over 6,500 hymns written by Charles Wesley (1707-1788), who with his brother John was founder of the Methodist movement in the Church of England.

‘Rock of Ages cleft for me, let me hide myself in Thee’.

Inscribed on the base of the headstone (G679) of John Dewhirst of Black Hill Bottom, Pecket Well, who died in 1911 aged 40, and his wife Ellen who died in 1937 aged 60. The hymn Rock of Ages, of which these are the first two lines, was written in 1776 by Augustus Montague Toplady, an Anglican cleric and Calvinist opponent of the teachings of John Wesley.

Rock of Ages was regarded as one of the Great Four Anglican Hymns of the 19th century, and was a favourite of Prince Albert, who asked for it to be played to him on his deathbed. It was recorded for Decca Records in 1949 by Bing Crosby, and included on his album Beloved Hymns.

It has been claimed that Toplady drew his inspiration from an incident in the gorge of Burrington Combe in the Mendip Hills. Toplady, then a curate in the nearby village of Blagdon, was travelling along the gorge when he was caught in a storm. Finding shelter in a gap in the gorge, he was struck by the title and scribbled down the initial lyrics.

The story most probably has no basis in fact, but the rock formation was subsequently named after the hymn anyway.

‘Father in thy gracious keeping leave we now our loved one sleeping’.

Inscribed on the base of the headstone (plot G704) of Daniel and Janet Thornton of Hebden Bridge and their daughter Ellen Gwendoline Thornton, who died in Storthes Hall psychiatric hospital in 1955, aged 62. The epitaph is the refrain from the hymn Now the Labourer’s Task is O’er, written in 1870 by John Ellerton, an Anglican minister who wrote or translated over eighty hymns.

‘Lord All Pitying, Jesu Blest, Grant Them Thine Eternal Rest’.

This epitaph is from the headstone (G675) commemorating David Greenwood of Carr Head Farm, Pecket Well, who died in 1906 aged 61, and his wife Sarah, who died in 1923 aged 78. Also commemorated is their son John Greenwood, who died in 1931 aged 64.

The epitaph is from the final couplet of the medieval Latin poem Dies irae (Day of Wrath):

‘Pie Iesu Domine, Dona eis requiem’.

Dies irae (the Day of Wrath) is a Latin sequence attributed to either Thomas of Celano of the Franciscans (1200–1265) or to Latino Malabranca Orsini (d. 1294).

The sequence dates from the 13th century at the latest, though it is possible that it is much older, with some sources ascribing its origin to St. Gregory the Great (d. 604), Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), or Bonaventure (1221–1274).

Centre panel from the triptych Last Judgment (c1467–1471) by Hans Memling.

The poem describes the Last Judgment, the trumpet summoning souls before the throne of God, where the saved will be delivered and the unsaved cast into eternal flames. It is best known from its use in the Roman Rite Requiem (Mass for the Dead or Funeral Mass). An English version is found in various Anglican Communion service books. The first melody set to these words, a Gregorian chant, is one of the most quoted in musical literature, appearing in the works of many composers. The final couplet, Pie Jesu, may have been added at a later date, and has often been used in settings of the Requiem Mass.

OTHER EPITAPHS

‘Afflictions sore long time she bore

Physicians strove in vain:

But death gave ease when God did please

And freed her from her pain’.

Jenny Tatham, wife of John Tatham, who died in Haworth on 14th July 1840 aged 60 (FY228).

This epitaph, or one of the many variations of it, occurs regularly in Britain, America and elsewhere, and dates back to around 1760, but there is no record of its author. Mark Twain mentions a similar epitaph in an 1870 article in The Galaxy on ‘Post-Mortem Poetry’, where he identifies it as an epitaph commonly used for ‘consumptives of long standing’. It is quoted in an American music hall song of 1865 called Oil on the Brain, and in David Copperfield Dickens refers to this epitaph being used on a monumental tablet in memory of a Mr Bodger.

‘This world is vain and full of pain

Of cares and troubles sore

But they are blest who are at rest

With Christ for evermore.’

The grave (CY273) of six members of the Bancroft family from Sowerby Bridge: John and Sarah Bancroft: their sons William, who died in 1851 aged 28, and John Bancroft jnr, who died in 1872 aged 44: their grandson Alfred (son of John jnr and Ellen Bancroft) who died in 1867 aged 7 months.

The sixth member of the family is not recorded on the headstone and is unnamed: the burial register records a burial in this grave on 30th May 1852 – ‘Wm Bancroft’s child‘, Sowerby Bridge, aged 5.

This is another epitaph that occurs elsewhere: a very similar epitaph is found on a headstone in Addingham churchyard (Dorothy Wall, who died in 1845 and her husband William who died in 1848), and it has also been recorded on a headstone in a cemetery in New Jersey from the 1860s.

In memory of Marianna, daughter of James and Marianne Greaves of Bacup, who died in 1855 aged 20. She is buried with her father, who died in 1866, in plot A504.

‘From infancy to blooming youth she grew,

As from the bud the flower expands to view,

When He who best knows how his own to save,

Resumed in love the boon his mercy gave.’

This epitaph is found in The Churchyard Manual (1851) by W. Hastings Kelke.

‘Though dead his name is precious still

And who his vacant place can fill

His voice still floats in memory’s ear

Like distant music, once how near

In fond remembrance yet he smiles

Thou from our home he’s lost awhile.’

John Kershaw of Black Hill, Pecket Well, who died in 1879 aged 28. His daughter Hannah died in 1899 aged 21, and his wife Sarah (born Crossley) died in 1902 aged 45 (B67a).

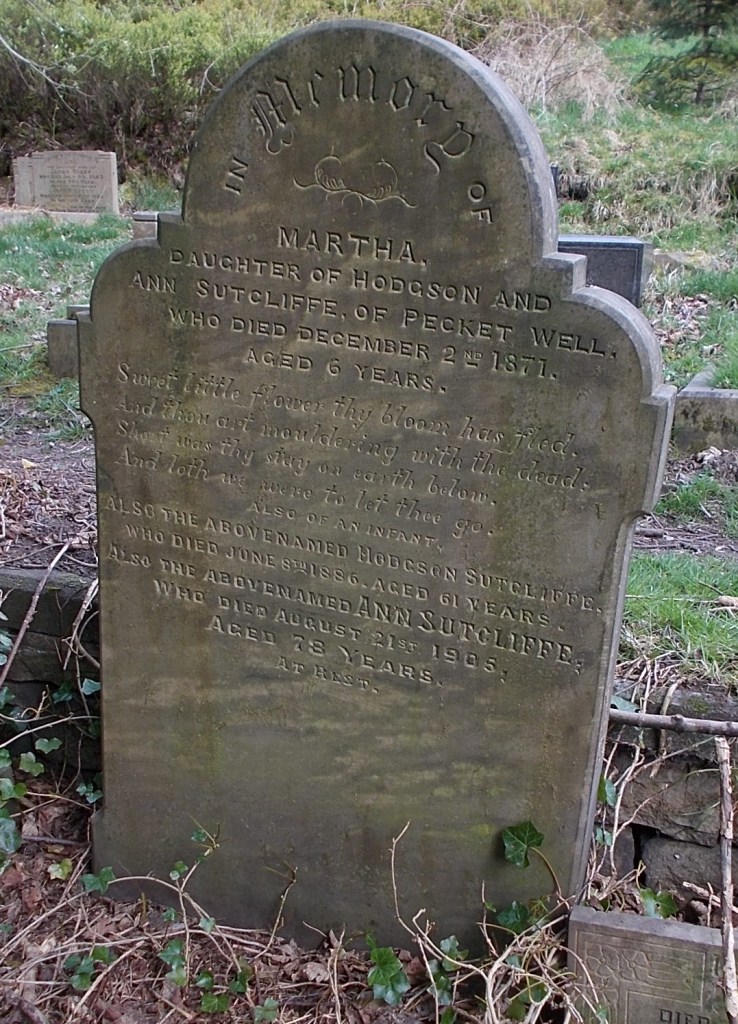

‘Sweet little flower thy bloom has fled.

And thou art mouldering with the dead:

Short was thy stay on earth below.

And loth we were to let thee go’.

‘In memory of Martha, daughter of Hodgson and Ann Sutcliffe of Pecket Well, who died December 2nd 1871 aged 6 years’.

Martha is buried with her parents, and also ‘an infant’, whose name, age and date of death are unknown (B32a).

‘His sufferings were very great

With grace he bore them all

But God has now removed his pain

And called his loved one home.’

John Keen of Foster Lane, Hebden Bridge, who died in 1879 aged 26. His wife Grace (born Greenwood) died in 1940, aged 84 (B68a).

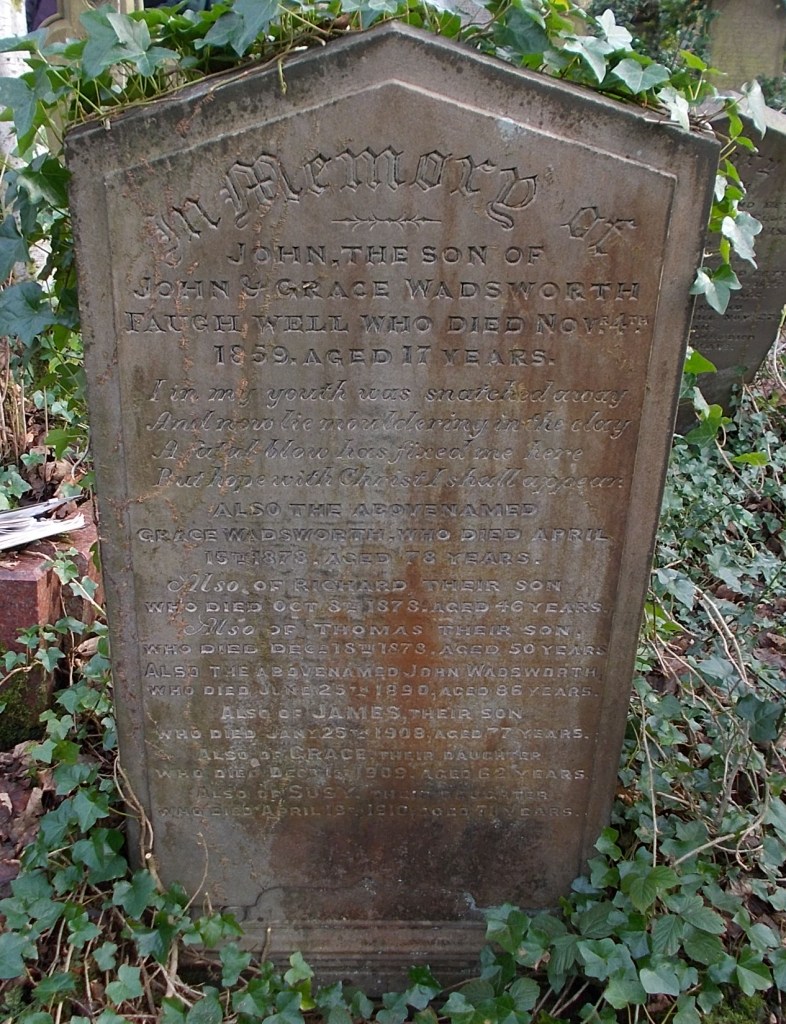

‘I in my youth was snatched away

And now lie mouldering in the clay

A fatal blow has fixed me here

But hope with Christ I shall appear.’

‘In memory of John, the son of John & Grace Wadsworth, Faugh Well, who died Nov 4th 1859 aged 17 years’ (A439).

‘How much suffering Heaven knows.

But now she’s free from all her woes;

She’s passed through Jordan’s swelling flood.

And landed safe with Christ her God.’

Hannah Ashworth died in 1891 aged 74. Her husband Richard Ashworth of Holmes Terrace near Rawtenstall, died in 1887 aged 71 years (B199a).

‘Darts of pain and pangs of aching

Long endur’d have ceased at last:

And the sleep that knows no waking.

Waits the Great Archangel’s blast’.

Esther Moss, daughter of Joseph Haigh Moss and Jane Moss (born Moorhouse) died in 1855 aged 27, and these lines were written by her father for her funeral card.

Another son Alfred Moss, who died in 1859 aged 27 is also commemorated on this headstone (A456).

Joseph Haigh Moss was the author of a number of poems, and a collection of them – Miscellaneous Poems by the late J.H.Moss was published in 1862, shortly after his death.

The origin of the epitaph (OY26) to William Sutcliffe, who died in 1820 aged 46, is unknown, but identical or similar texts occur in Wibsey, Bradford (William Fox, who died in 1861 aged 44) and Kalgoorlie, Western Australia (1915).

‘Slowly his earthly frame decay’d

His end was long in sight

Nor was his steady soul afraid

To make its awful flight.’

His wife Sally died in 1834 aged 56. Her epitaph reads:

‘Her flesh rests here till Christ shall come to claim his treasure from the tomb’.

On a slightly more cheerful note, the inscription on the gravestone of Grace Chatburn (FY219) hints at a long life well lived and a peaceful death: an epitaph that most of us would probably be more than happy to have on our gravestone.

‘Here rest the mortal remains of Grace Chatburn of Sprutts. After a most exemplary life she gently expired, May 18th 1834 in the 87th year of her age.’

‘Meek was his temper, generous was his mind.

A faithful husband and a father kind:

No greater gift to woman ever given.

No greater loss unless the loss of heaven’.

Joseph Shackleton, who died in 1861 aged 43. His son William, who died in 1860 aged 22 is buried with him (A435), but there is no mention on the headstone of Joseph’s wife Jane Shackleton, and no record of her in the burial register (although she may have remarried and changed her name). The headstone says that the family lived at Holmefield, Northowram but the burial register records Joseph and William living at Ovenden.

‘Farewell my wife and children dear,

I’ve toiled with you for many a year:

I always strove to do my best,

But now I’m gone to take my rest’.

William Wadsworth of Garden Street, Hebden Bridge, died in 1876 aged 51. His daughter Martha Grace died in 1884 aged 18, another daughter Mary Ann died in 1888 aged 25, and his wife Mary died in 1893 aged 67 (B76a).

A similar epitaph for Mary Redman of Pecket Well, who died in 1878 aged 56.

‘Farewell husband and children dear,

I am at rest, you need not fear:

Weep not for me nor sorrow take,

But love each other for my sake.’

Also commemorated on the headstone (A522) are her husband George Redman, who died in 1899 aged 76 and their son Greenwood, who died in 1864 aged 16.

This epitaph is for John Pickles of Chiserley Terrace (formerly of Boston Hill), who died in 1915 aged 70. Also mentioned on the headstone (B29a) is his wife Sarah, who died in 1891 aged 47.

‘His face we loved is now laid low,

His fond true heart is still.

His vacant place remains to us,

That none can ever fill’.

John Pickles bought the plot in 1872, when he and his wife buried an unnamed child, and in 1881 they buried an unnamed stillborn baby. Neither infant is recorded on the headstone.

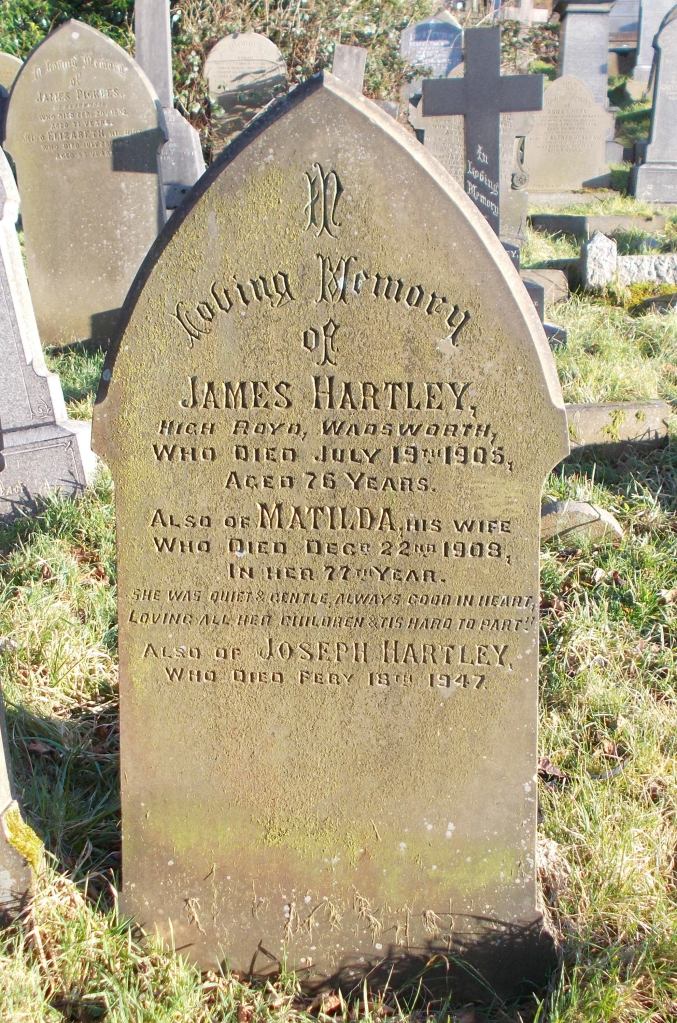

‘She was quiet & gentle, always good in heart,

Loving all her children & tis hard to part’.

The epitaph for Matilda Hartley of High Royd, Mytholmroyd, who died in 1908 aged 77: her husband James Hartley had died in 1905 aged 76.

Also commemorated is their grandson, Joseph Hartley of Todmorden, who died in 1947 aged 70 (B341a)

‘A tender wife, a mother dear, has left me and my family here:

Left me in a world of sin, hope to meet her in Heaven again’.

‘Her End was Peace’.

The epitaph of Emma Winearls, who died in 1906 aged 57. Buried with her (Plot B1181) is her husband Alfred Hastings Winearls, who died in 1914 aged 63.

Emma (born Emma Mott) and Alfred were both born in Norfolk.

The first part of Alfred Hastings Winearl’s epitaph is one which is found on many other gravestones (there are two more at Wainsgate (the Tatham family grave at Plot B30a, and the Harwood / Collinge grave at B286a/287a), and it is found on at least one CWGC headstone), but the authorship is uncertain:

‘We cannot, Lord, thy purpose see

But all is well that’s done by thee’

The most likely origin of this phrase is probably the hymn O let my trembling soul be still, written by John Bowring. The first verse of the hymn ends with the lines:

‘I cannot, Lord, Thy purpose see;

But all is well, since ruled by Thee’

Sir John Bowring KCB FRS FRGS (1792-1872), also known as Phraya Siamanukulkij Siammitrmahayot, was a British political economist, traveller, writer, businessman, literary translator, polyglot and the fourth reformist Governor of Hong Kong. He was appointed by Queen Victoria as emissary to Siam, later he was appointed by King Mongkut of Siam as ambassador to London. He was a radical (if sometimes inconsistent) member of parliament, editor of the Westminster Review, an advocate of decimal currency, and friend of Jeremy Bentham. He was a Unitarian, and somehow found time to write 88 hymns.

‘My comrades dear you have shed a tear

For my poor body lying here.

My tender wife, my children dear

I must lie here till Christ appear’.

‘Through faith she willingly resigned

Her earthly tenement to dust

In sure and certain hope to find

A resurrection with the just’.

The epitaphs of William Redman of Midgehole, who died in 1814 aged 64, and his wife Sarah Redman, who died in 1827 aged 74 (FY229).

‘Who plucked this flower?’ said the gardener;

‘I’ said the Master, and the gardener held his peace.

This is an old epitaph, several versions of which can be found in a number of Victorian epitaph collections (a variation is found in W.H.Kelke’s The Churchyard Manual of 1851):

‘Who plucked my choicest flower?’ the gardener cried;

‘The Master did,’ a well-known voice replied;

‘ ‘Tis well! they are all His,’ the gardener said’

And meekly bowed his reverential head.

An identically worded epitaph is found on a gravestone in Faversham, Kent, commemorating three children who died in 1856, 1858 and 1862 (from Frederick Maiben’s An Original Collection of Extant Epitaphs). The same publication, published in 1870, also contains another variation found in Highgate Cemetery, dated 1854:

‘Who plucked this flower?’ said the

Gardener, as he walked round his

garden: one of his fellow-labourers

said, ‘It is the Master.’

The Gardener held his peace.

The version found at Wainsgate is on the base of the memorial (B258a) to Fred and Lily Ann Arundel, their son Edward, who died in 1897 aged 2, and their daughter Elsie, who died in 1925 aged 22:

‘Who plucked these flowers, the master and the gardener held his peace’.

This rather garbled abbreviated version makes little sense, but interestingly, almost identical wording is found on a 1918 CWGC headstone in Gaza War Cemetery, commemorating a young British soldier, private Nathan Whitehead from Tebay in Westmoreland who died of dysentry aged 23, while serving with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in Palestine during WW1.

The authorship of this epitaph is unknown – it may have been written by W.H.Kelke, but it was probably collected by him from an unnamed source. One possibility is that it is derived from the writings of Puritan Presbyterian minister and author John Flavel (1627-1691), who wrote:

‘If we pluck a rose in the bud as we walk in our gardens, who will criticize us for it? It belongs to us, and we can cut it off when we please. It is the same in your situation. Your sweet bud, which was cut off before it was fully grown, was cut off by him who owned it, by him who created and formed it.’

This epitaph is from the gravestone (OY120) of two children of Robert and Amy Ashworth of Crimsworth: Thomas who died in 1793 aged 2 years, and their daughter Amy, who died in 1797:

‘Come my dear aged parents now

And take a view of me

Call back your mispent time to mind

That you may sleep with me’.

We don’t know what became of Thomas and Amy’s parents, or whether or not they heeded their children’s warning.

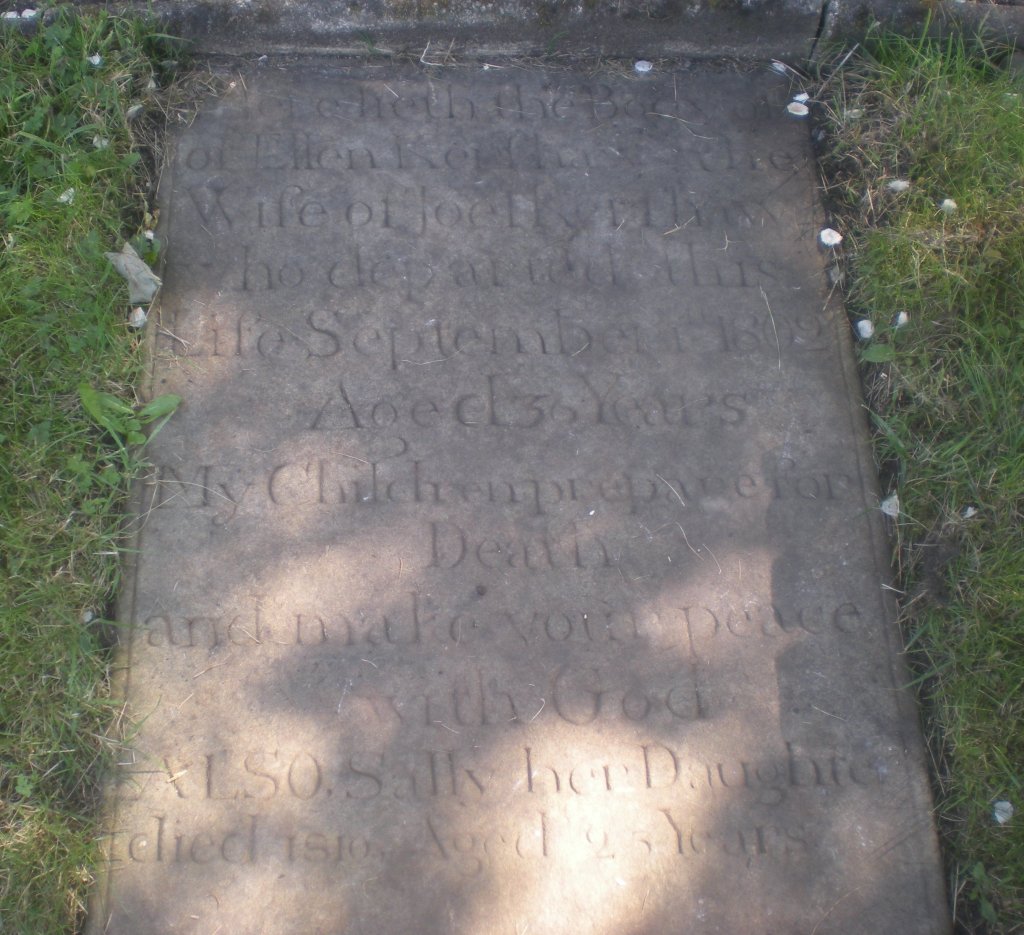

The previous epitaph is written as a message from dead children to their parents. Another epitaph found at Wainsgate on the gravestone of Ellen Kershaw (OY79) takes the form of a message from a dead mother to her children:

‘My children, prepare for death and make your peace with God.’

Ellen Kershaw, wife of Joel Kershaw of Boston Hill, died on 1st September 1802 aged 36 – her daughter Sally died in 1810 aged 25, and is buried with her mother.

This epitaph is also found on the gravestone of Mary Crossley (OY53) and her sons James, who died in 1834 aged 73 and William, who died in 1838 at the age of 80.

‘TOLD YOU I WAS ILL’

Inscribed on the headstone (H1055) of Colin Newbitt (1950-2017), and attributed to Spike Milligan. This epitaph is commonly believed to be inscribed on Milligan’s headstone, but this is not strictly true.

Terence Alan Patrick Sean ‘Spike’ Milligan KBE (1918- 2002), was buried in the graveyard at St.Thomas’ Church, Winchelsea, East Sussex. He had said that he wanted his headstone to bear the words ‘I told you I was ill’, but the Chichester diocese refused to allow this rather irreverent epitaph, so as a compromise it was translated into Gaelic: Dúirt mé leat go raibh mé breoite. Milligan’s father was Irish, and he became an Irish citizen in 1962.

In a 2012 survey by Marie Curie Cancer Care, Spike Milligan’s epitaph was voted the nation’s favourite – ahead of ‘Either these curtains go or I do’ (Oscar Wilde) and ‘The best is yet to come’ (Frank Sinatra).

It turns out that Wilde probably said no such thing – his last words were possibly ‘My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has got to go’, but even that is disputed. The epitaph on his tomb (by the sculptor Jacob Epstein) in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris is from his poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol:

‘And alien tears will fill for him,

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn’.

* * *

In 2018 the family of Margaret Keane, an Irish woman who had lived in the UK, sought permission to have an inscription in Gaelic on her headstone in the graveyard of St.Giles parish church in Exhall near Coventry: In ár gcroíthe go deo (In our hearts forever). The diocesan Consistory Court ruled that the inscription must be accompanied by an English translation, on the grounds that it might be regarded as ‘some form of slogan’ or ‘a political statement’, a decision that was greeted with astonishment not only by the family but also by the Anglican hierarchy. The decision was overturned in 2021 by the Court of Arches, the highest ecclesiastical court in Britain.

LITERARY EPITAPHS

‘The single rose

Is now the garden

Where all loves end’

This quotation from Ash Wednesday by T.S. Eliot is inscribed on the monument by sculptor Charles Gurrey commemorating Eve Clements (1990-2018).

Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888-1965) is interred at St.Michael & All Angels’ parish church, East Coker, Somerset. The epitaph on his memorial plaque, taken from his Four Quartets reads:

‘In my beginning is my end. In my end is my beginning‘

The epitaph on his memorial plaque in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey taken from Little Gidding reads:

‘The communication of the dead is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living’

Photograph by Charles Gurrey

‘WE GIVE BIRTH ASTRIDE OF THE GRAVE

THE LIGHT GLEAMS AN INSTANT

THEN IT’S NIGHT ONCE MORE’

Samuel Beckett by Hugo Jehle

Engraved on a brass plaque on the grave (D1019) of Elaine Connell (1953-2007). The quote comes from Waiting for Godot by the ever cheerful Samuel Beckett.

Beckett’s own grave, in Montparnasse cemetery, Paris, is marked by a simple grey granite slab (Beckett had specified that his memorial should be “any colour, so long as it’s grey”), inscribed with only the names and years of birth and death of himself and his wife Suzanne.

‘The supreme happiness in life is the conviction that we are loved.’

The epitaph on the headstone (K723) of Janice McGroarty, who died in 2013 aged 61, is from Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (1802-1885). The full quotation (although translations vary) is usually given as:

“The supreme happiness in life is the conviction that we are loved; loved for ourselves, or rather in spite of ourselves.”

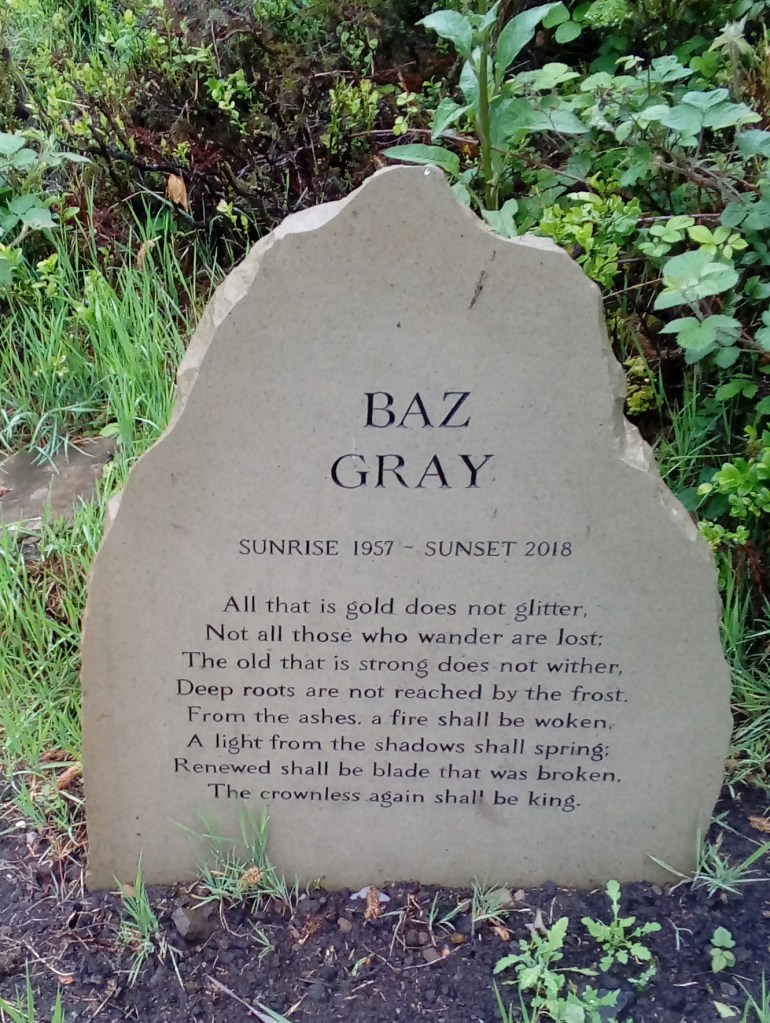

Margaret Veronica Gray (1936-2022) was buried next to her son Stewart ‘Baz’ Gray (1957-2018) and daughter Wendy Ann Gray (1963-2022). Her headstone has two literary epitaphs:

‘Not a Day Slipped Away’

In an interview with The Telegraph in 2014, bestselling author Penny Vincenzi (author of 17 novels with worldwide sales of over 7 million copies) was asked what her epitaph would be and this was her reply. Vincenzi died in 2018, aged 78 – she apparently requested a woodland burial next to her late husband, so there may not be a memorial with this inscription marking her grave.

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love:

A violet by a mossy stone

Half hidden from the eye!

—Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

The other epitaph is the second verse of the poem She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways, written in 1798 by William Wordsworth (1770-1850). The poem is one of a collection of five ballads called The Lucy Poems, written between 1798 and 1801, most of which were first published in the Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The subject of the poems is a young woman called Lucy (possibly fictitious, possibly based on a real person – perhaps his sister Dorothy) who dies an early death. Wordsworth is said to have sought to write this series of poems in ‘unaffected English verse infused with abstract ideals of beauty, nature, love, longing, and death’.

‘All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king’

The quotation on the headstone (G1193) of Margaret’s son, Stewart ‘Baz’ Gray (1957-2018) is from The Fellowship of the Ring by J.R.R.Tolkien.

‘When the journey’s over, there’ll be time enough to rest’

Grave I894 commemorates James Cherry, who died in 1971 aged 63, and his wife Violet Annie Cherry, who died in 1976 aged 70. There are also two small polished granite plaques maeking the interment of the ashes of their son and daughter: Tony Cherry died in Penticton, British Columbia, Canada in 2013, aged 76 and Rita Gillies died in London in 2010, aged 78.

The epitaph above, which is inscribed on Tony Cherry’s plaque seems to be from Reveille by A.E.Housman, the fourth poem in his 1896 collection A Shropshire Lad, but is not exactly the same as Housman’s lines: whether this is deliberate or a mistake is not known. The correct wording of the last verse of the poem is:

Clay lies still, but blood’s a rover;

Breath’s a ware that will not keep.

Up, lad: when the journey’s over

There’ll be time enough to sleep.

‘To Live is Miracle Enough’

The epitaph on the headstone (D1037/1038) of John Ludlam (1949-2021) is the title of a poem by Mervyn Peake.

Mervyn Peake (1911-1968) was a writer, artist, poet, and illustrator, best known as the author of what is usually referred to as the Gormenghast trilogy. The first line of the poem is inscribed on the headstone of his grave at St. Mary the Virgin, Burpham, West Sussex, where he is buried with his wife Maeve.

To live at all is miracle enough.

The doom of nations is another thing.

Here in my hammering blood-pulse is my proof.

Let every painter paint and poet sing

And all the sons of music ply their trade;

Machines are weaker than a beetle’s wing.

Swung out of sunlight into cosmic shade,

Come what come may the imagination’s heart

Is constellation high and can’t be weighed.

Nor greed nor fear can tear our faith apart

When every heart-beat hammers out the proof

That life itself is miracle enough

The headstone on the grave (H1053) of Margaret Biller (1945-2016) has no literary epitaph, but tells us that:

She Loved Literature

Presumably the epitaph was chosen by her husband, John Edward Biller, who died in 2020 aged 80 and was buried with Margaret at Wainsgate.

The CHURCHYARD MANUAL & LYRA MEMORIALIS

The Churchyard Manual intended chiefly for Rural Districts was written in 1851 by W. Hastings Kelke, rector of Drayton Beauchamp in Buckinghamshire, with the object of ‘the improvement of rural churchyards’. As well as chapters on Cemeteries, Churchyard Memorials and Embellishment, it includes a list of 501 suggested epitaphs suitable for Christian churchyards, arranged in categories which include Infancy; Youth; Missionaries; Naval and Military Men; Servants; After lingering Illness or severe Suffering; Deaf, Dumb, Blind etc.; Violent Death and The Lost at Sea.

‘The Collection of Epitaphs, it is hoped, will be found an acceptable aid towards improving the character of such inscriptions…….The Epitaphs, collected from various sources, have in many instances been considerably altered, not with the presumption of improving the originals, but to render them more simple, or to adapt them to the purposes of memorial inscription.’

The epitaphs in The Churchyard Manual are from various sources, including biblical quotations and epitaphs taken from Lyra Memorialis, a collection of ‘Original Epitaphs and Churchyard Thoughts in Verse’, by Joseph Snow. The 2nd edition (1847) of Lyra Memorialis, which includes an Essay upon Epitaphs by William Wordsworth, states in the preface that:

‘The object of this volume is not to furnish hyperbolical compliment or stilted panegyric, but to suggest, as regards the dead, immortal hopes, to mourners, a sedate sorrow, and to the general reader, earnest and solemn admonition’.

Digitized copies of both books are available free from Google books (books.google.com).

An ORIGINAL COLLECTION of EXTANT EPITAPHS, gathered by a Commercial in spare moments

A collection of epitaphs first published in 1870 (‘published by request‘) by Frederick Maiben, a commercial traveller from London. The epitaphs were collected from churchyards and cemeteries across the South of England and the Midlands while Maiben was travelling, during his ‘evening strolls’ and ‘while waiting for conveyances from stage to stage’. He had always been fascinated by churches and churchyards, and being employed to ‘go on the road’ gave him an opportunity to copy these epitaphs ‘for his own amusement’, which he was eventually persuaded to publish.

The epitaphs in this collection were chosen on the basis of:

‘…..their human interest, their quaintness, and in a few instances their mere oddity’.

Those commemorated include Phoebe Hessel (who served in the British Army disguised as a man and died in 1821 aged 108), John Bailes from Northampton (who died in 1706 at the age of 126), Nanette Stocker (a musical hall star, at 33 inches tall the ‘smallest woman ever in this kingdom’, who died in 1819 aged 39), Sake Deen Mahomed (a British Indian who opened the first Indian restaurant in England in 1810) and Thomas Tipper (famed brewer of Old Stingo from Newhaven, West Sussex).

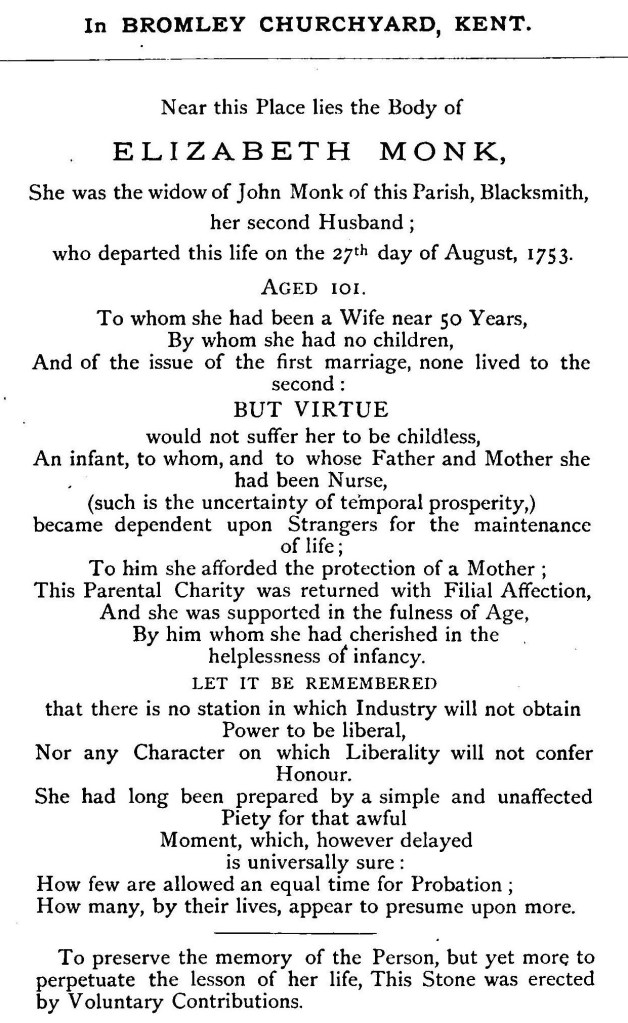

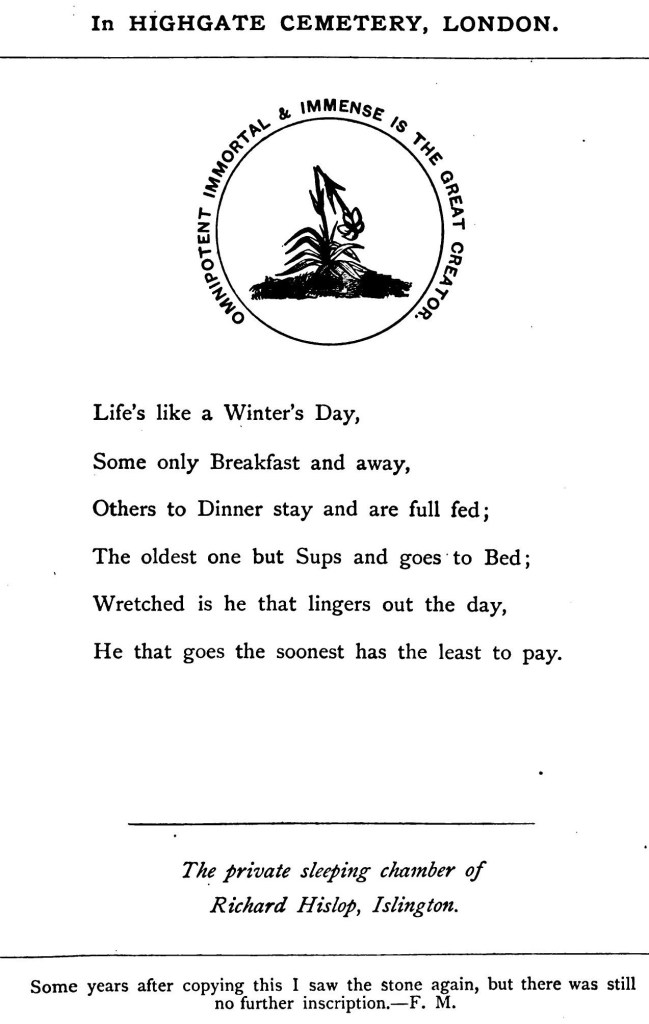

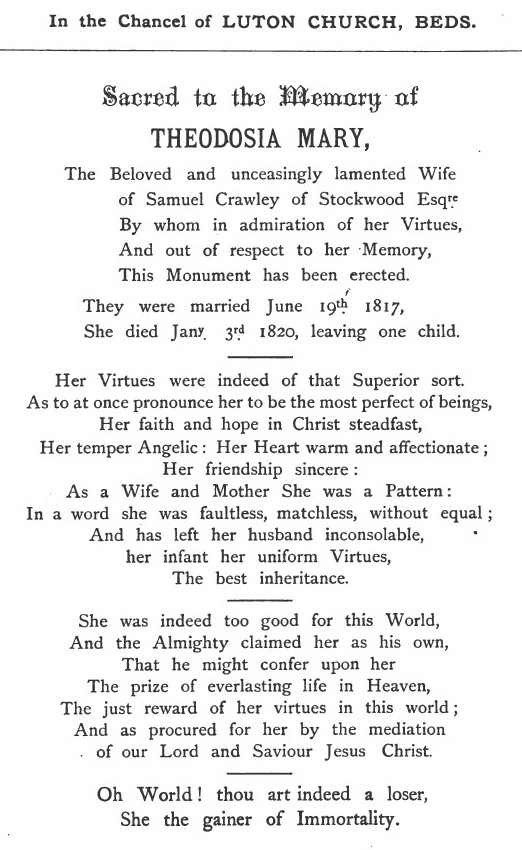

Here a few examples of the epitaphs included in Maiben’s collection:

The ‘old Stingo’ mentioned in Thomas Tipper’s epitaph was the generic name for a type of strong beer. Hudibras was a satirical poem, written in a mock-heroic style by Samuel Butler (1613-1680), and published in three parts in 1663, 1664 & 1678. The action is set in the last years of the Interregnum, around 1658–60, immediately before the Restoration in May 1660. The story tells of the adventures Hudibras, a knight and colonel in the Parliamentary army, and his squire Ralpho, the narrative form derived from Don Quixote.

A digitized copy of this book is available free from Google books (books.google.com).

* * *

Taken from Frederick Maiben’s An Original Collection of Extant Epitaphs, gathered by a Commercial in spare moments.

The spelling may be less than perfect, but the message is all too clear.